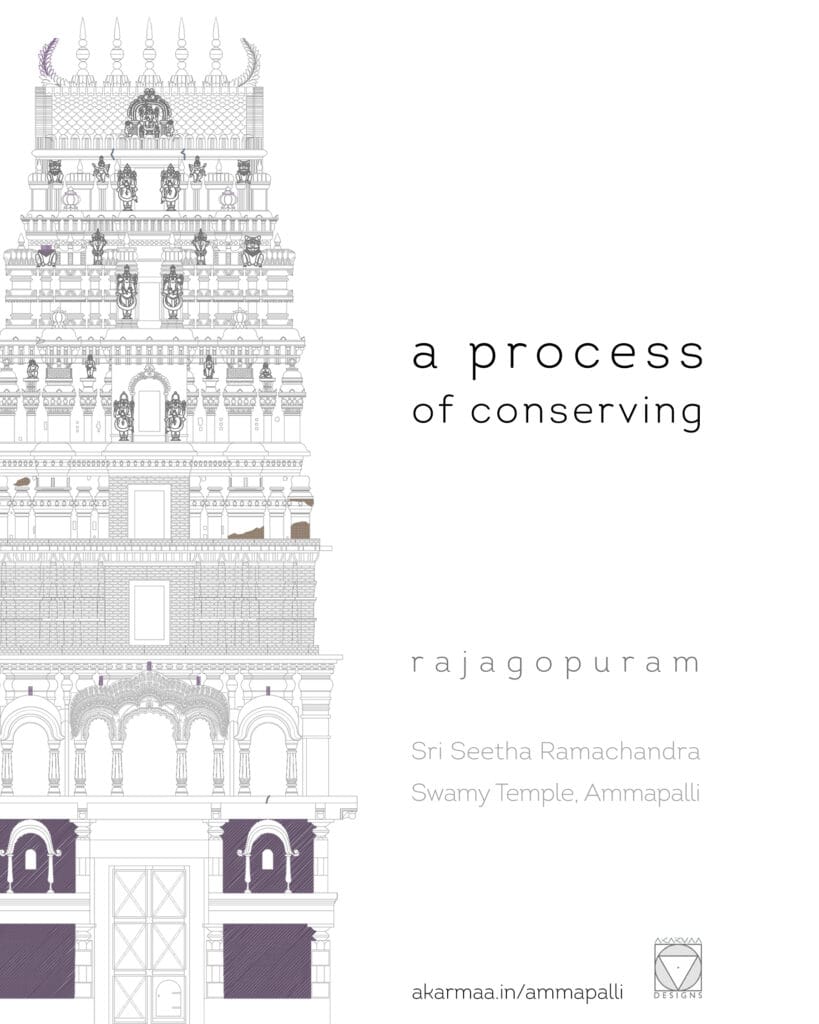

Rajagopuram of Sri Seetha Ramachandra Swamy Temple, Ammapalli

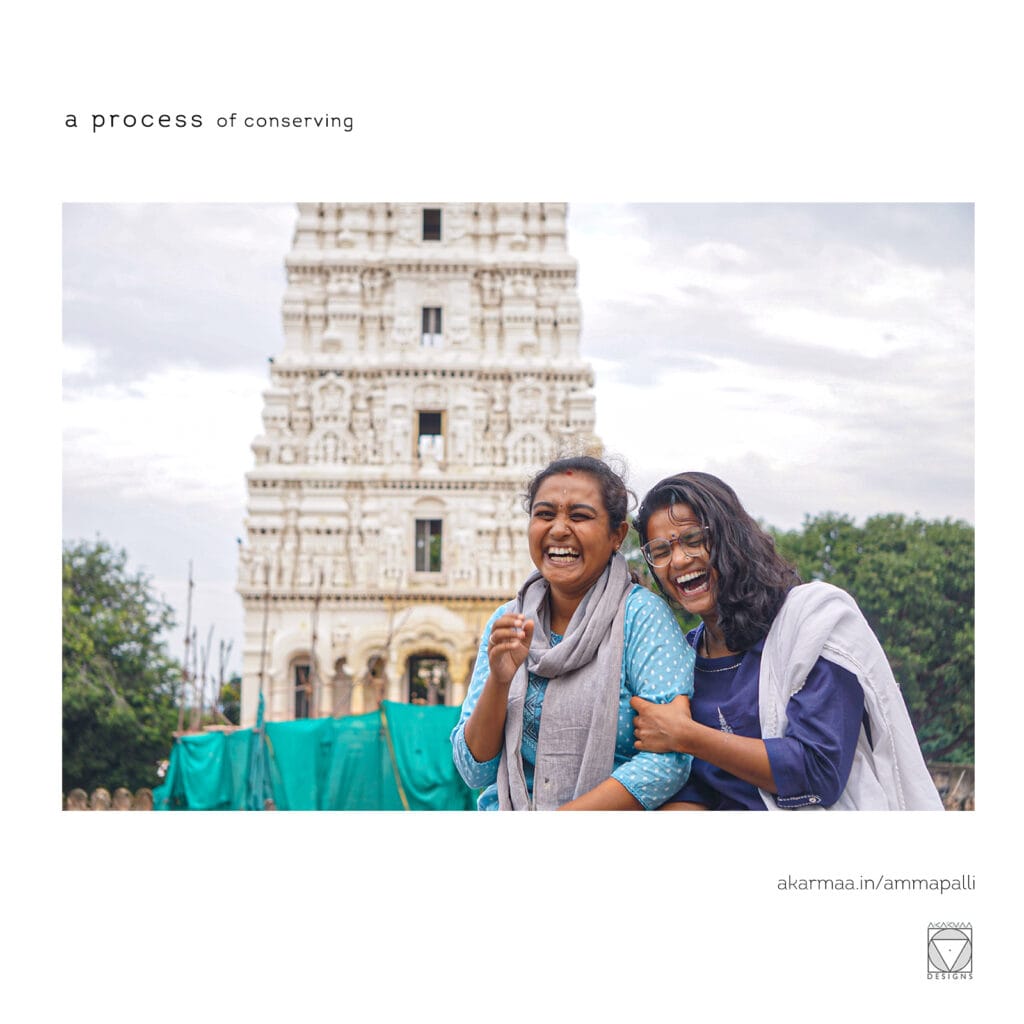

Dedicated to the hands which lay the invisible foundation stones of the Gopurams.

We don’t show what we make, we only talk about what are the thoughts that go around because that is what can share. You can make your buildings in your own way. They look different, they will be different, that’s fine but we have to share our knowledge in a way in which we are talking about processes rather than projects. Projects we’ll make I mean that is our joy and that we do, out of sheer animal instincts but we also need to share processes.

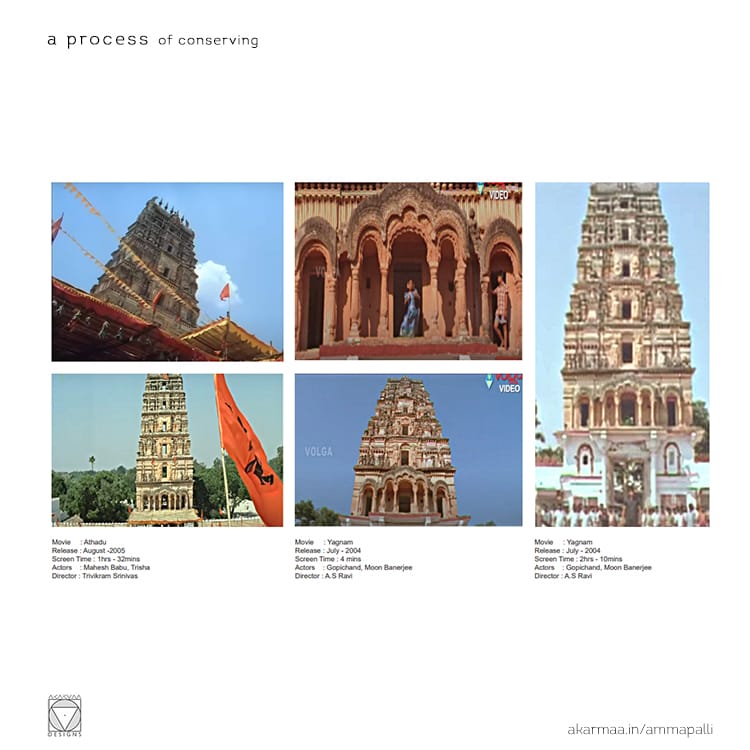

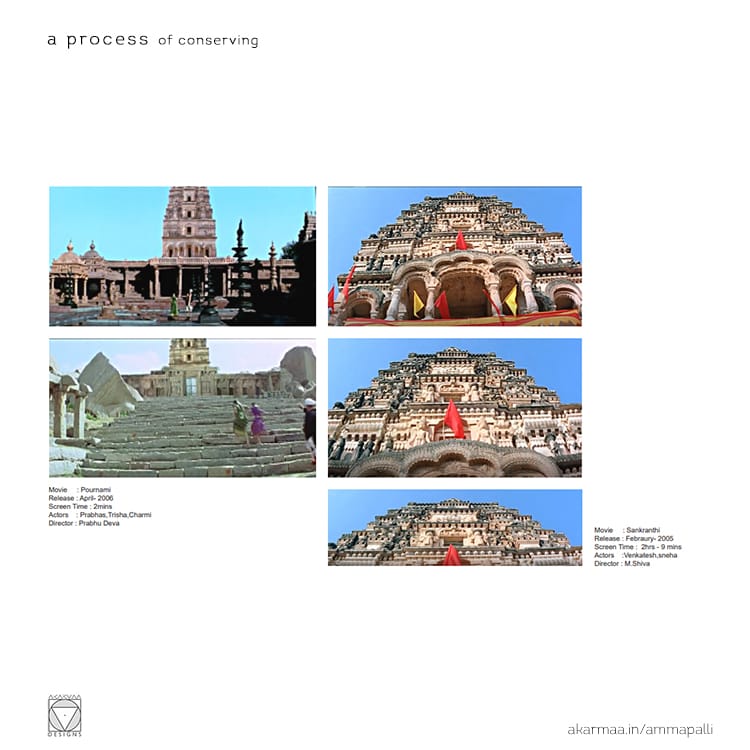

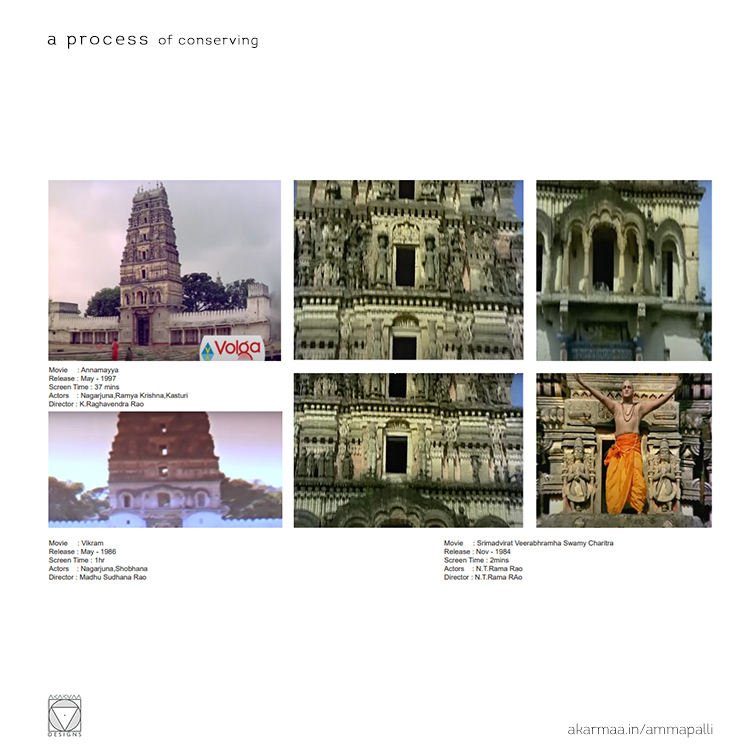

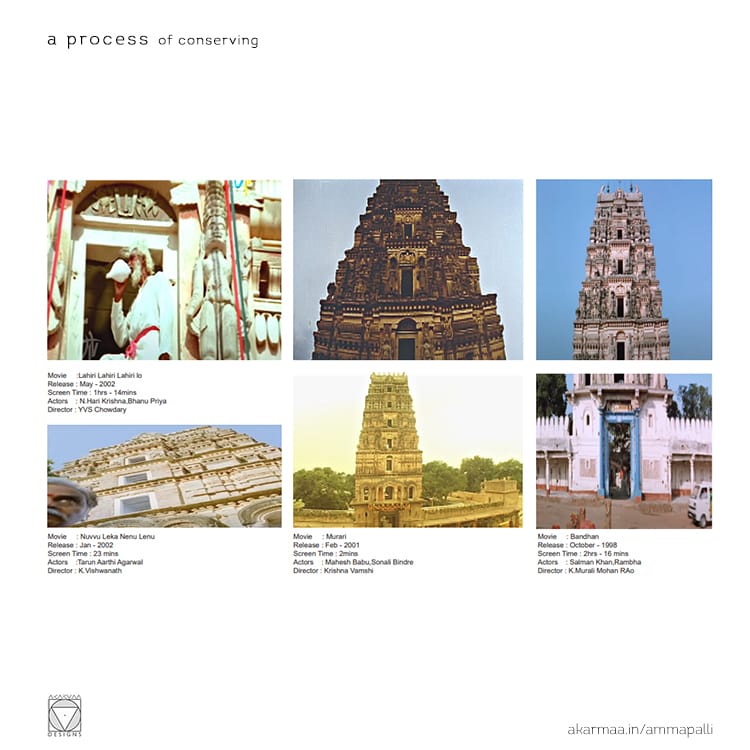

“Ikkada shooting cheste, cinema super hit-aee..!!” A Telugu dialogue loosely translates to “If we film here, our cinema will definitely be a great success”.

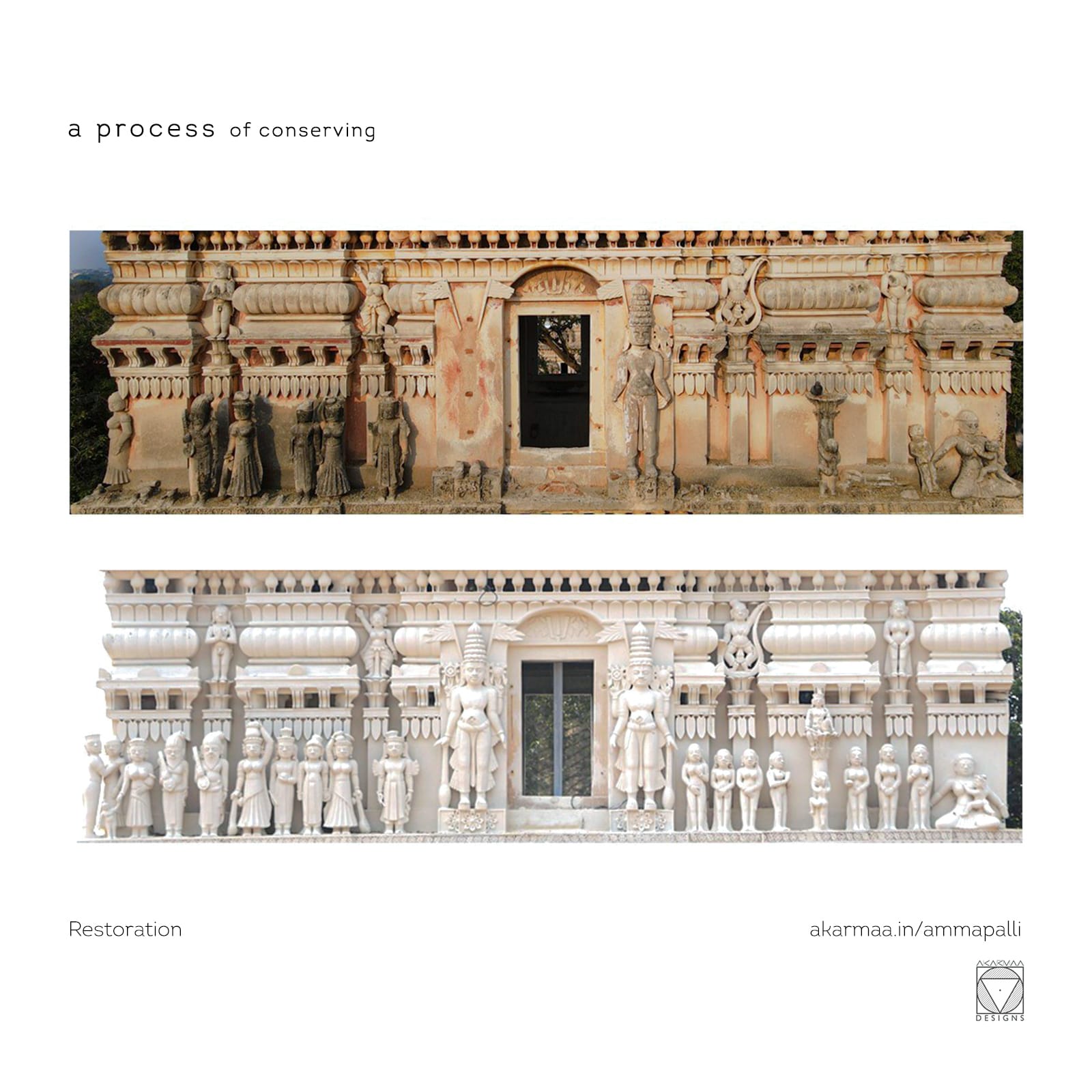

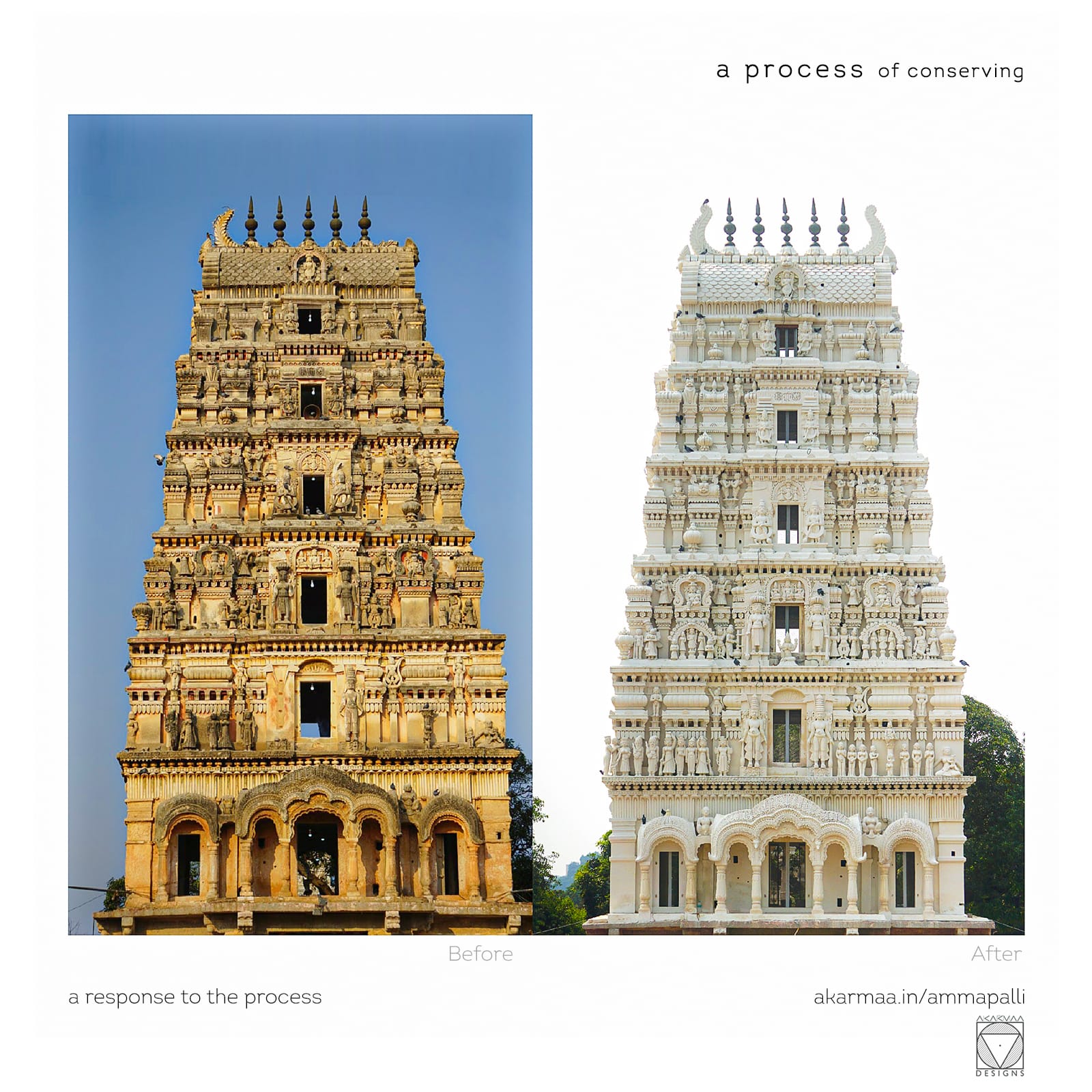

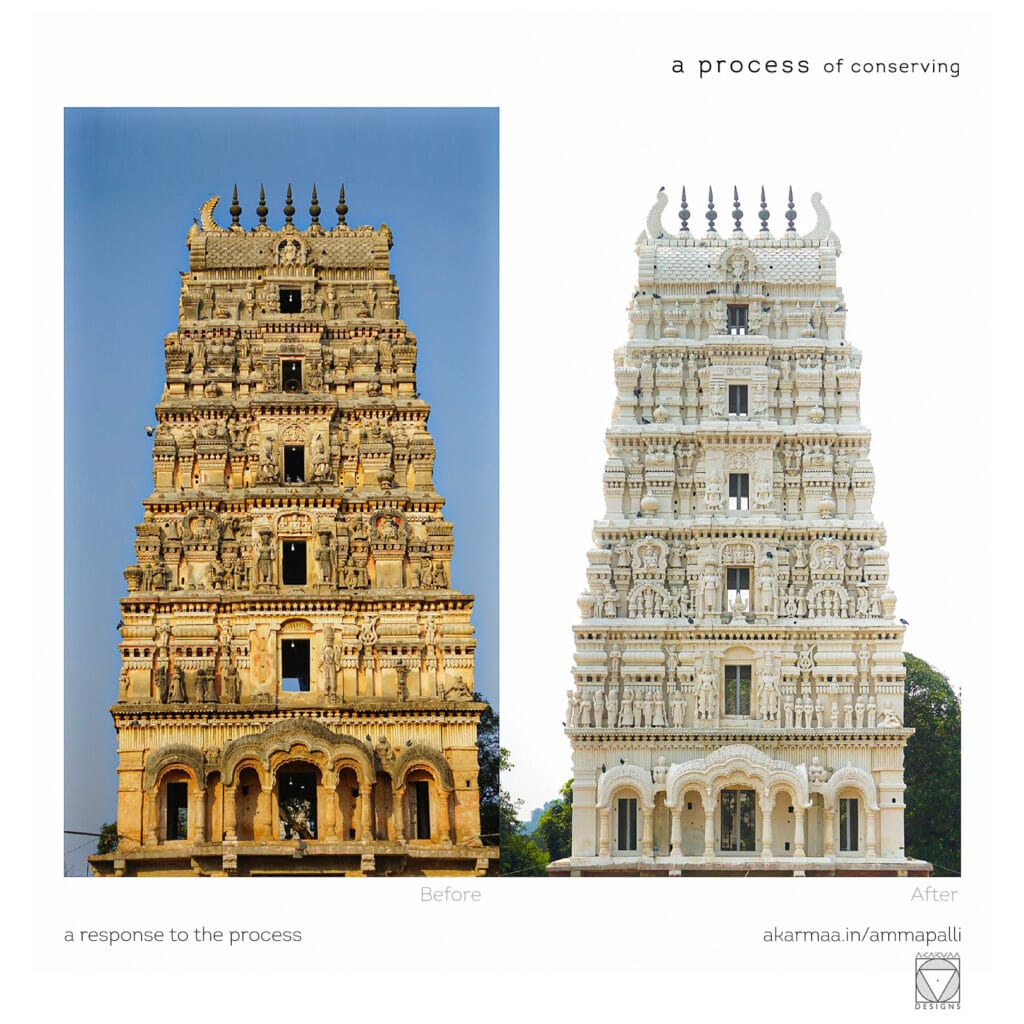

A locally known, desolate place with minimal to no visitors; served the aesthetic, spatial and privacy requirements of the cinema industry. For decades it gathered crowds only to see the actors and the actresses, while the triad of gods stood witness. The temple complex and especially the Raja-gopuram attributed to its splendour has been subject to different roles and respective cosmetic treatments; painted black to look like an old stone, nails hammered to accommodate props, wires running through weep holes and across the sculpture’s hand, legs and neck to place speakers, support poles to place light, etc. The structure thus has been subject to uncontrolled vandalism for decades. A scene of a car blow-up, where unfortunately the gas cylinder explosion sent the car flying onto the temple wall, damaging the structure; marked the termination of film shooting.

Located 32 km from Hyderabad, as the name suggests Sri Rama, Mother Sita and Brother Lakshma are the preceding deities of the Sri Seetha Ramachandra Swamy Temple. The trios are sculpted independently in black stone. Each of the idols is in standing postures, with simple clothes, bow and arrows, with thoranam embellished in floral patterns and with a kirtimukha crowning the arch. The thoranam of Rama is specially decorated with smaller figurines from the Dashavataram tales.

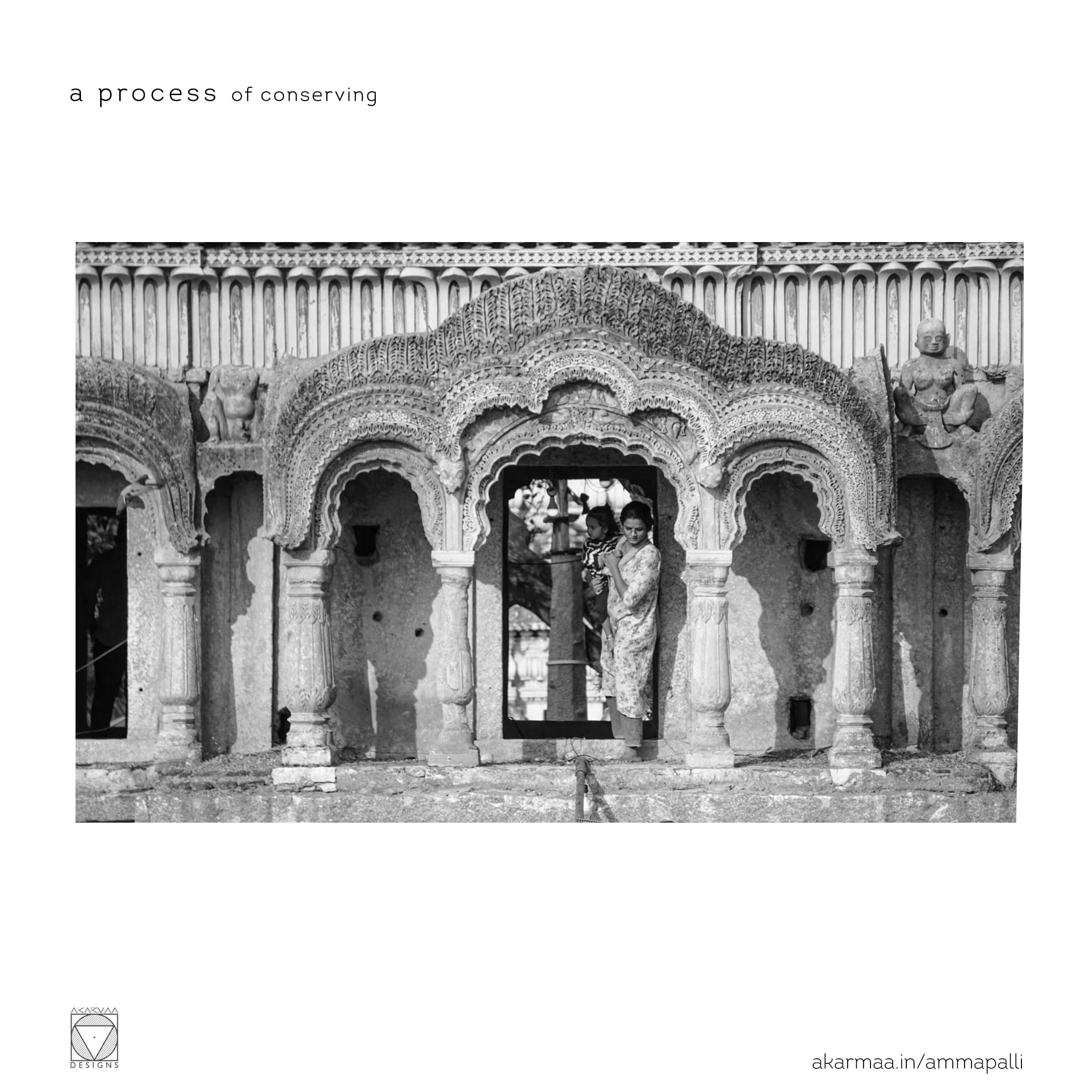

The three idols placed in the sanctum sanctorum are led to by a small antarala, an ardha mandapa, enveloped by an enclosed pradakshina patha leading from the mukha mandapa. This arrangement is enclosed by an open-to-sky aisle on four sides; which is further enclosed by a collonaded of corridors with central access doorways on four sides, a gopuram towering the entrance on the east side and rooms at the four corners, that become bastion-like rectangular rooms at the first floor. The outer walls of the corridor extend to the first floor and form merlons like in a fort.

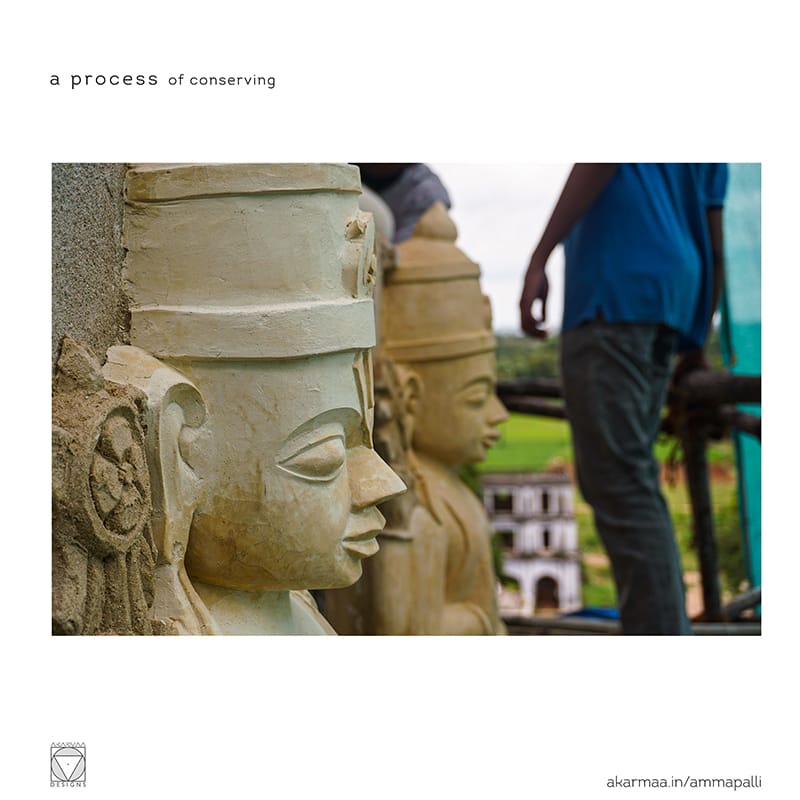

It was fascinating to learn from the archaeologists the process of deciphering the sculptural styles. What initially looked like a style of the Eastern Chalukyas was credited to the Kalyani Chalukyas, attributing to the crowning of the lion face on the thoranam. It also befitted the oral histories of the sculptural lineage from the 12th century AD. Further inspection suggested that the sculptures were an imitation of the style of the Kalyani Chalukyas and that they could not be older than the 16th century. The technical reports date the temple to the early 17th century.

The temple sits on about 200 acres of land, protected by high walls and allied structures in its surroundings. This enclosed complex has reminiscences of a secret staircase from the terrace to the ghadi, where the zamindars who patronised the construction resided. However what continues to exist is the entrance gateway from the north of the temple towards the ghadi, one shrine dedicated each to Lord Shiva, Hanuman and Ganesha; towards the north-east is one stepwell and another to the west of the temple. There is also a stone enclosure for a tall chariot, a kitchen, a mandapam towards the east, a two-tier entrance arched entranceway, a couple of houses, a mandapam for diyas and a rama-nama hundi.

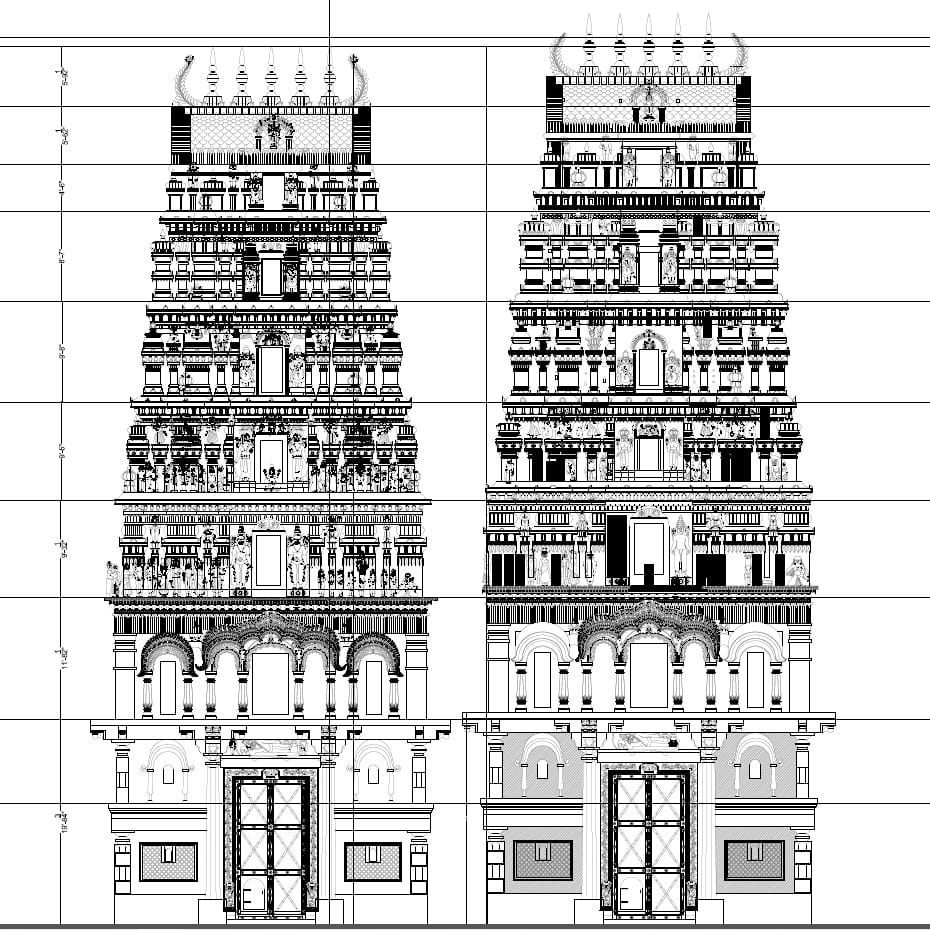

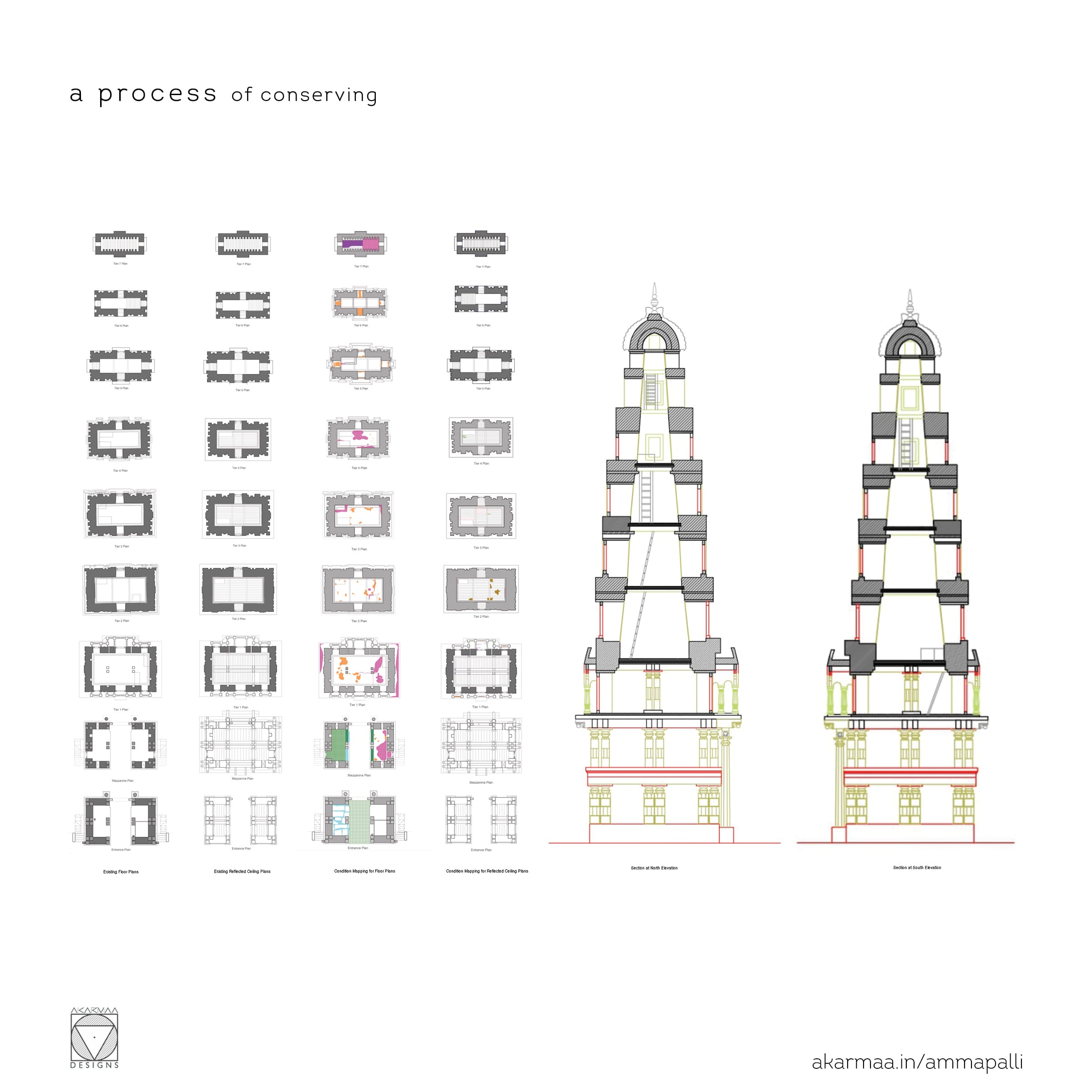

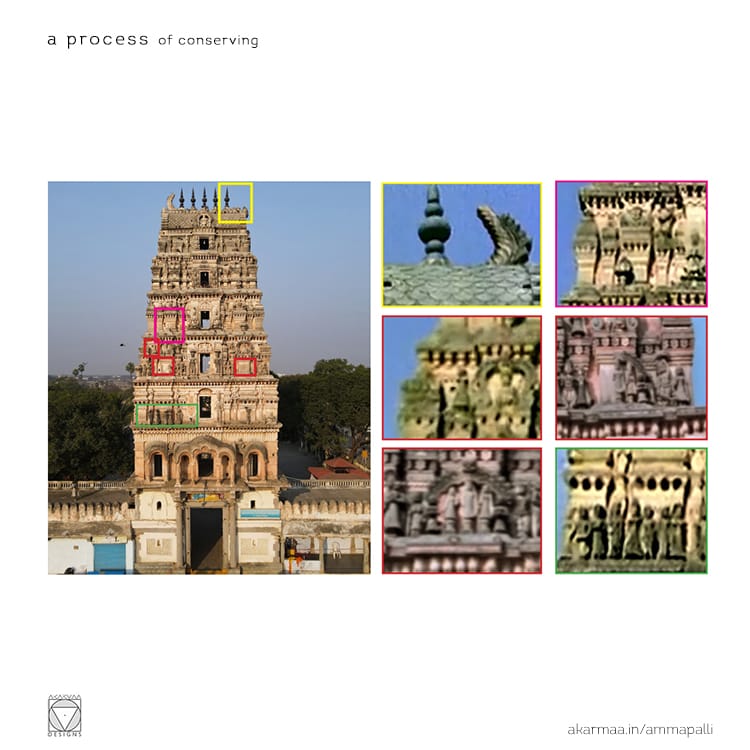

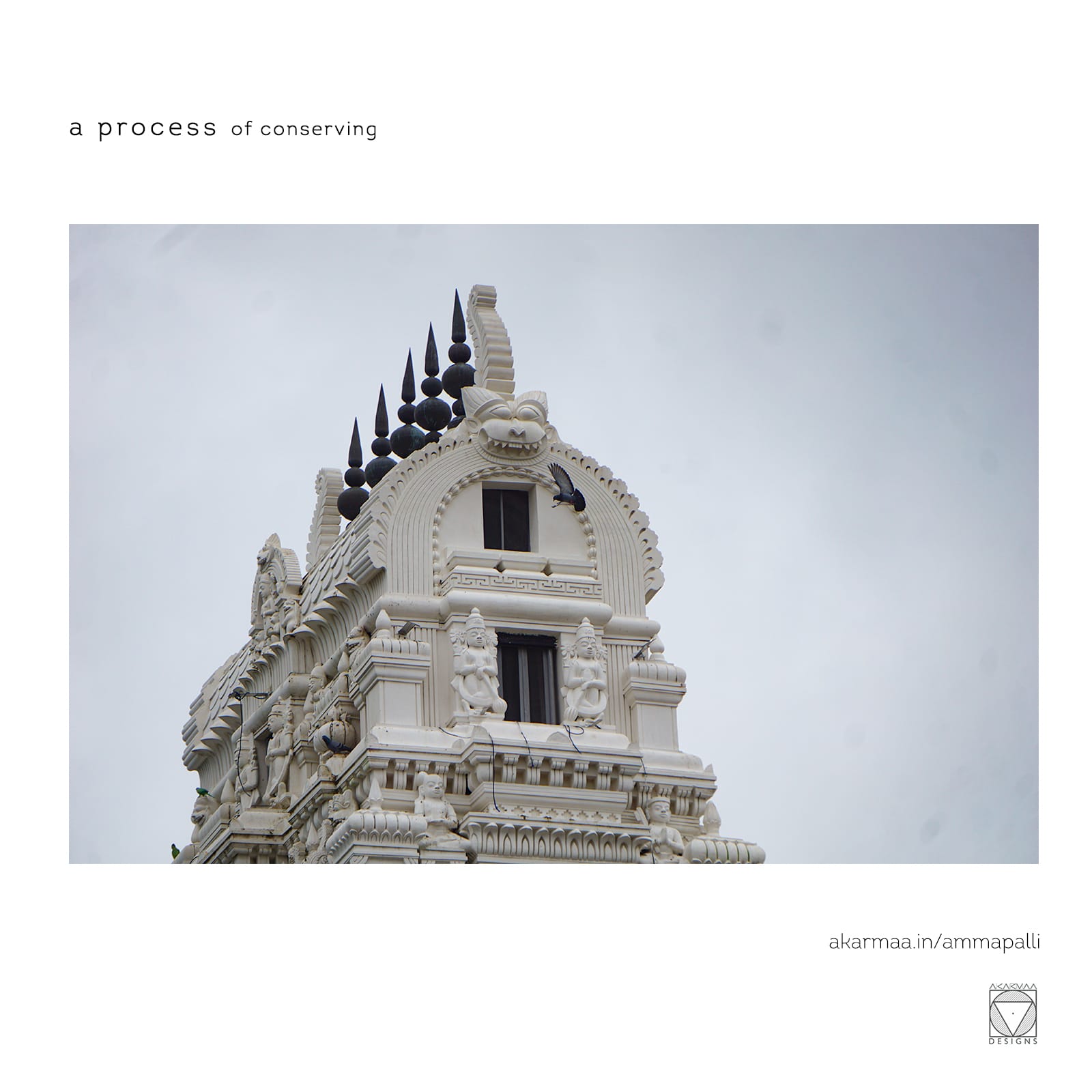

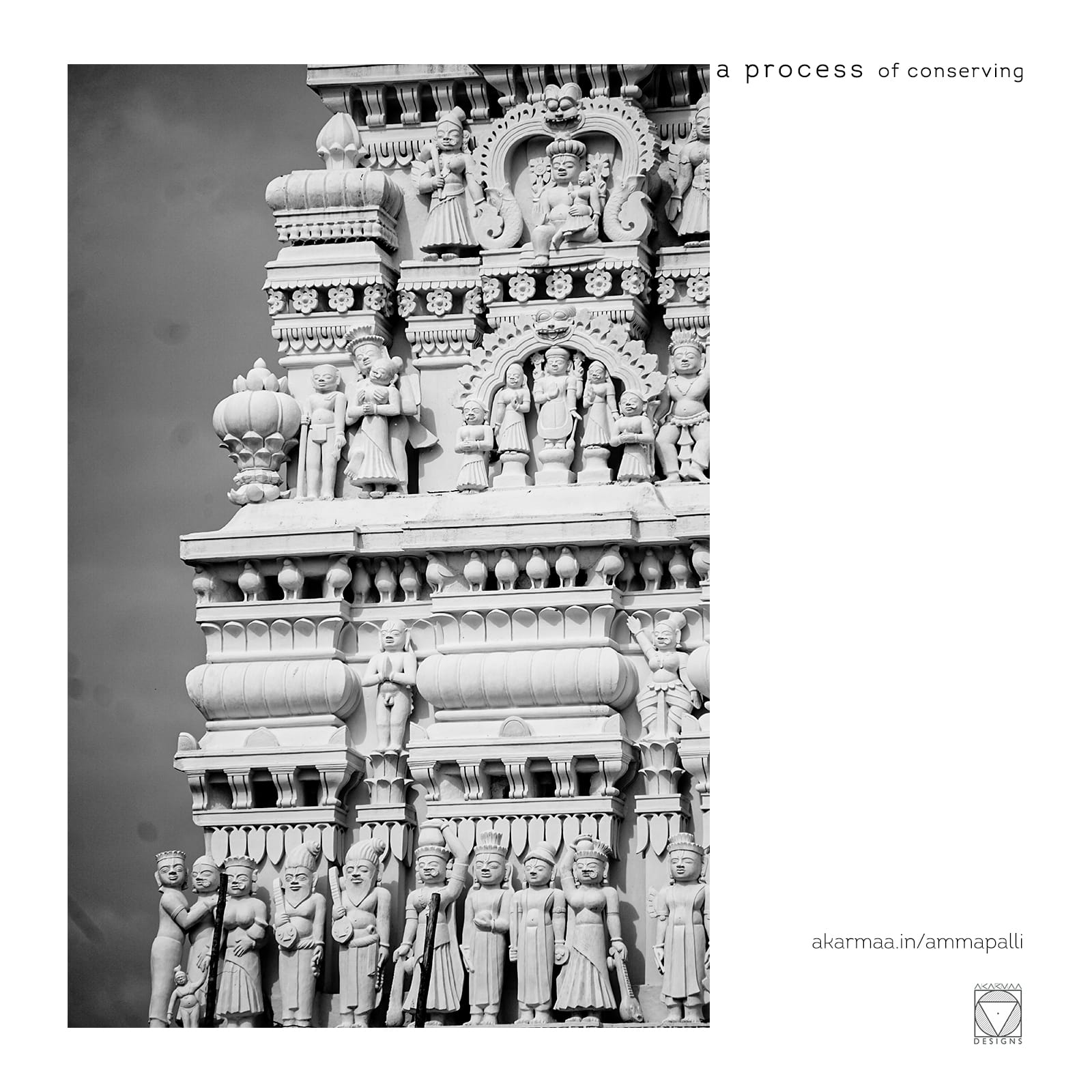

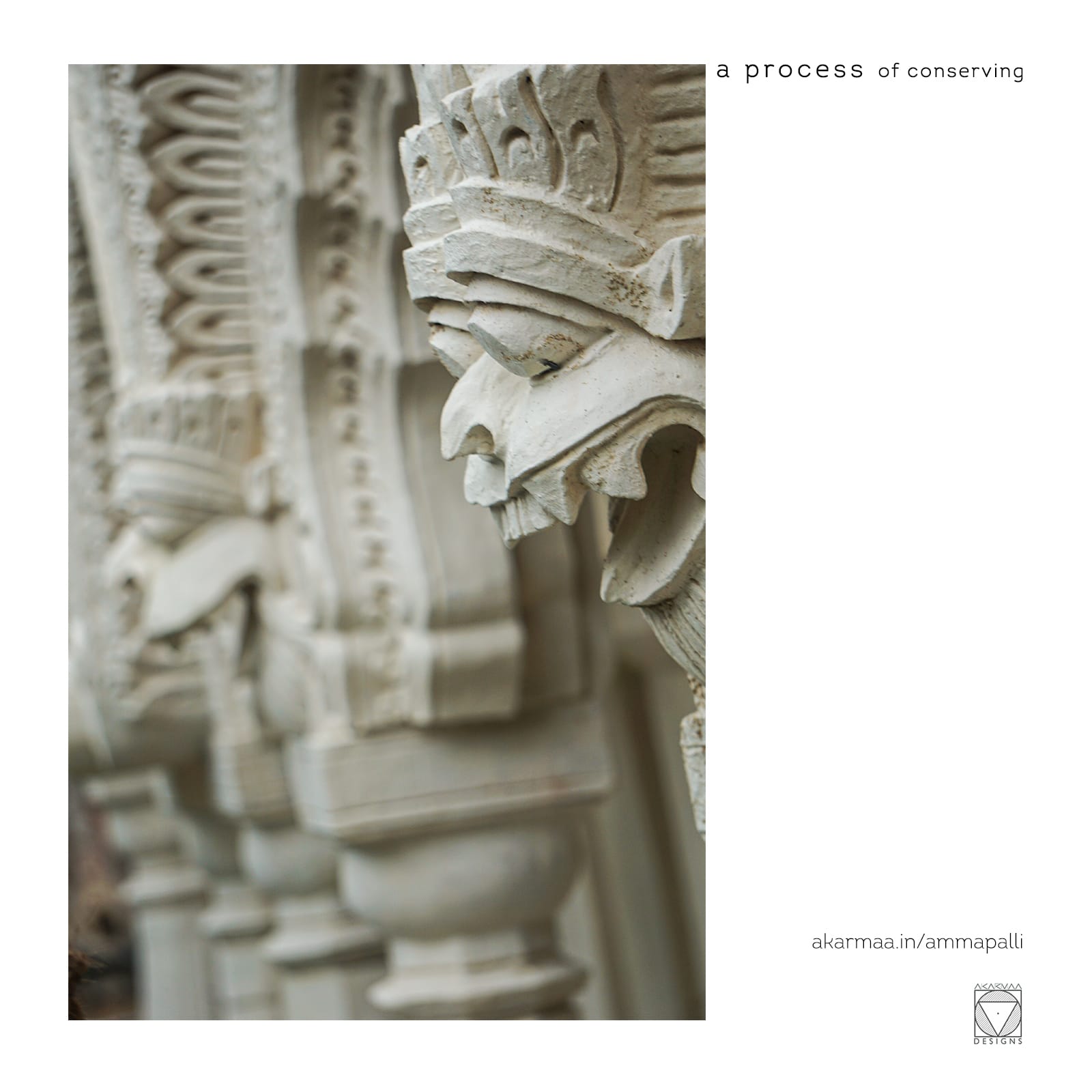

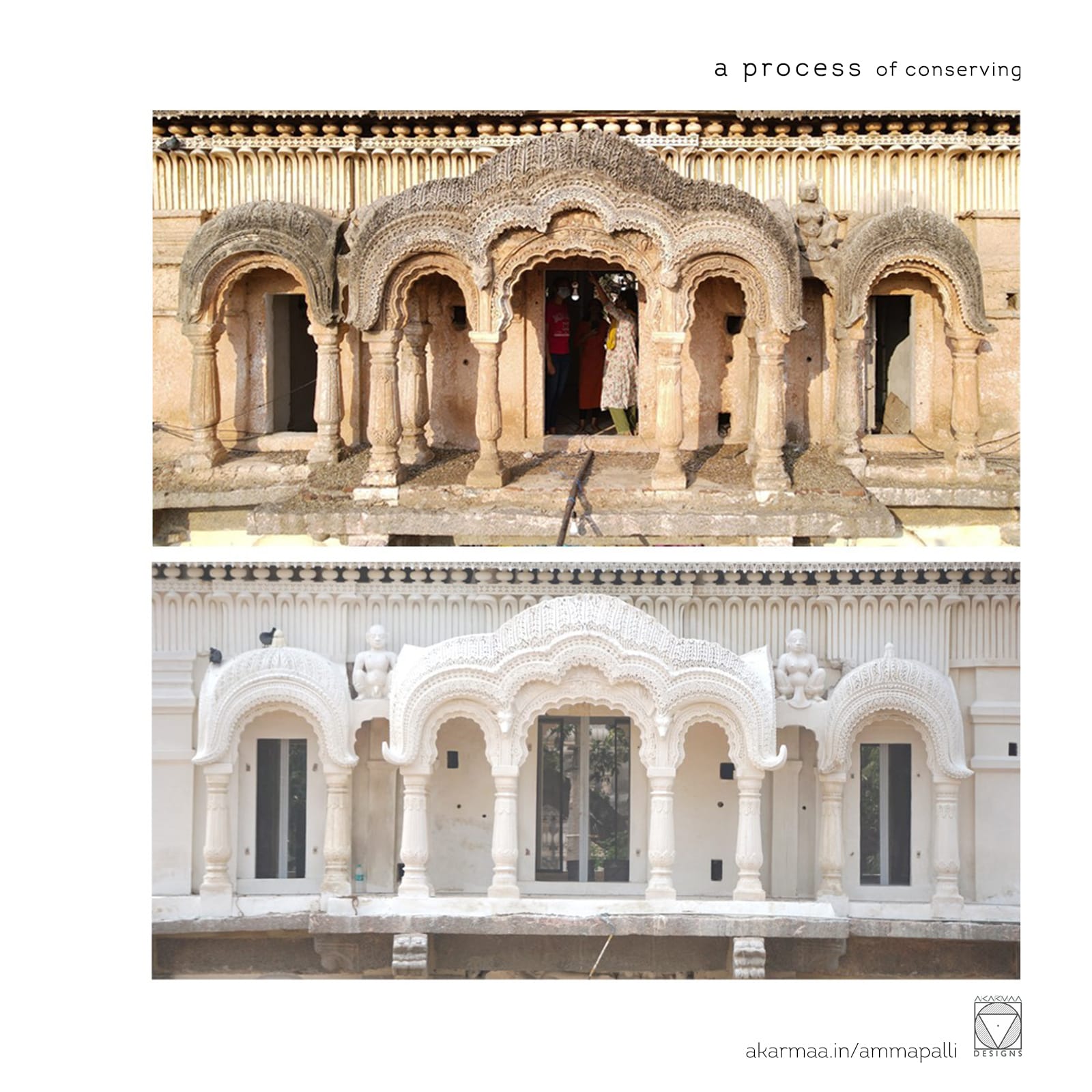

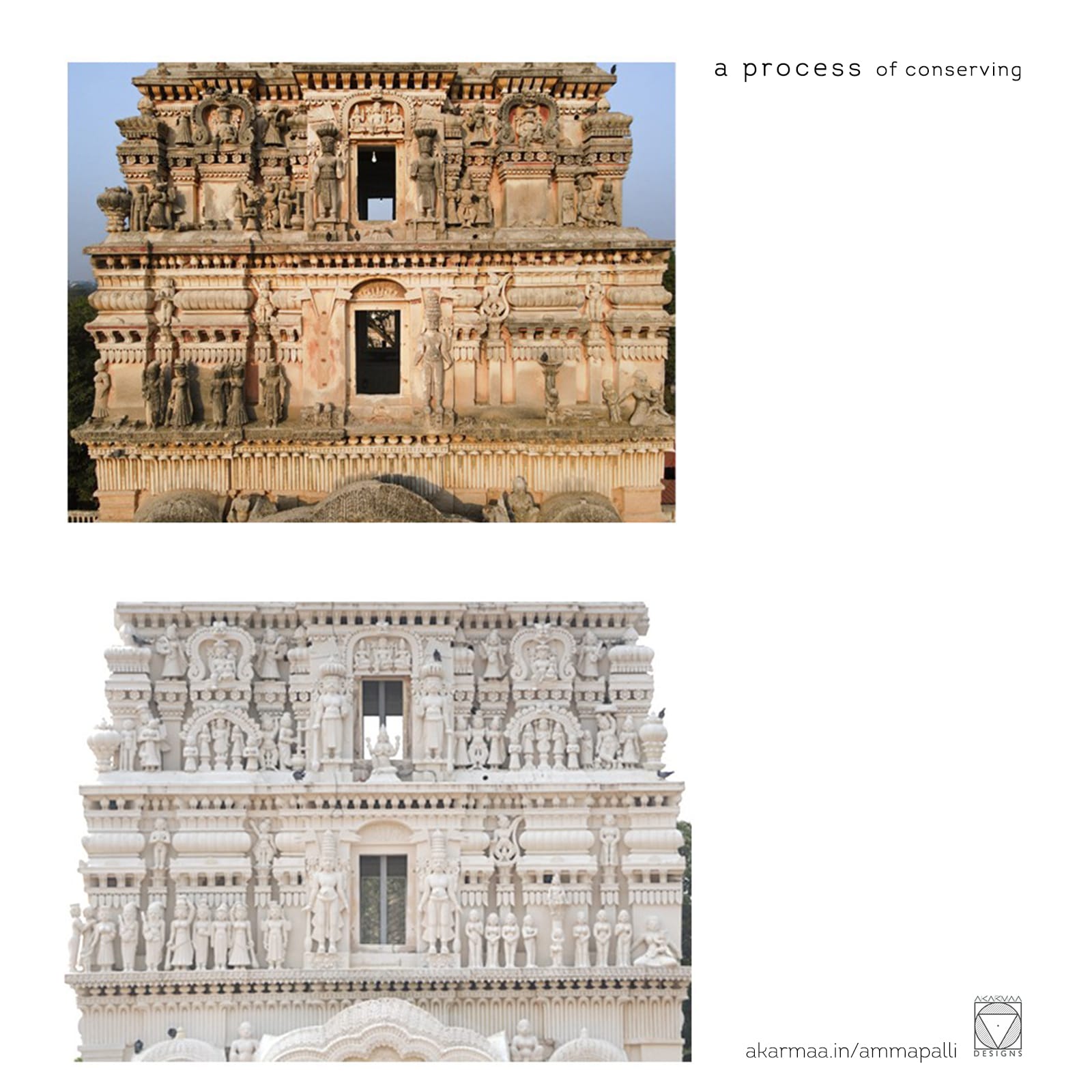

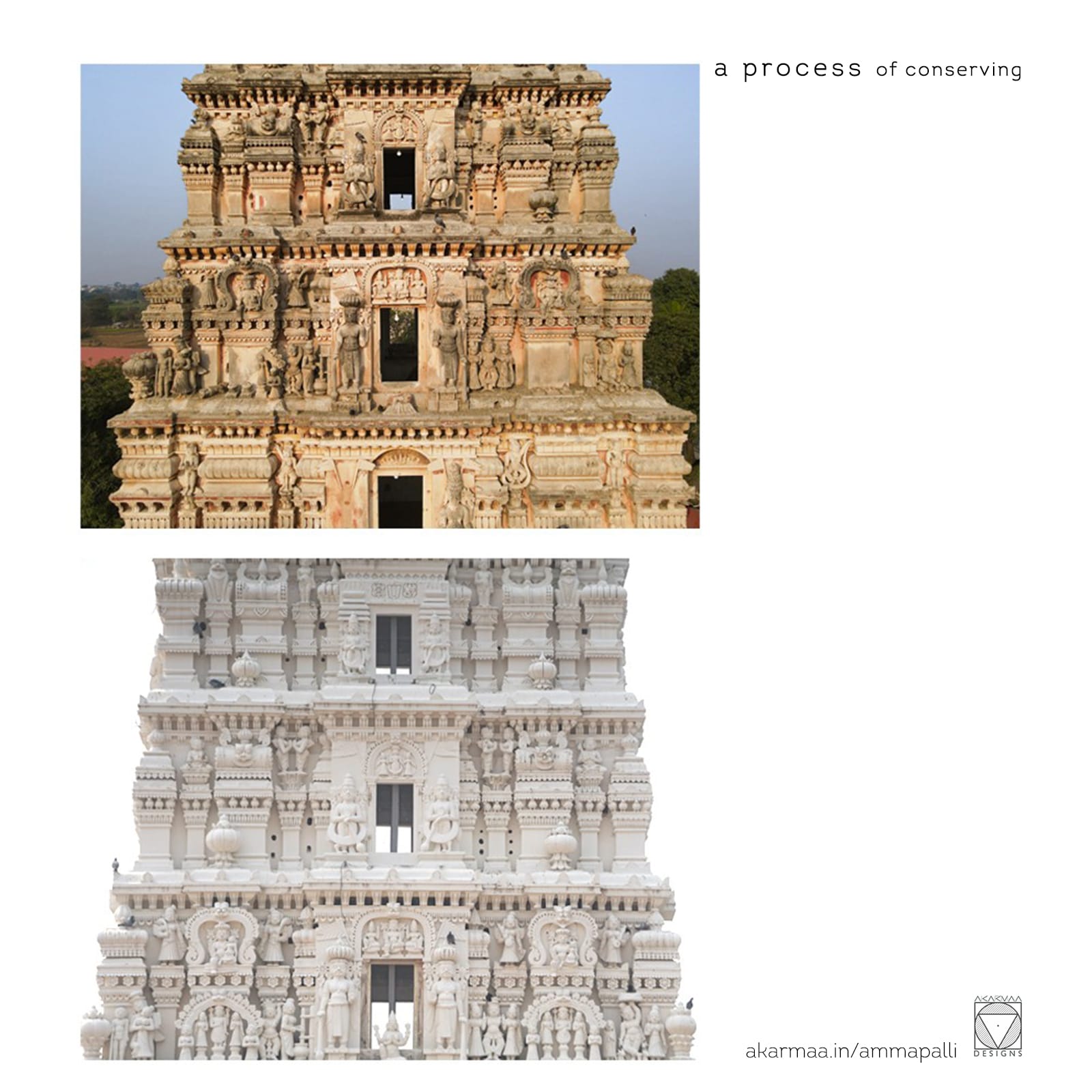

The different structures are connected by a bilane that leads to a large open ground in their midst with a sprawling 7-tired, 90-foot-tall Raja-gopuram forming the eastern entrance of the temple. The facades of the tiers in the Rajagopuram are intricately crafted with flora, fauna, imitation of mythical creatures and naked human figurines. Tier 1 being the most ornamented of all, has a tripartite arrangement of Jharokhas with double doors on each. Tier 2 has the story of Krishna’s Childhood like Gopika Vastraharan, Bala Krishna, Rakshasi Putana, Radha Krishna, Krishna with Mother Yashoda; while tier 3 has a story of Krishna lifting Govardhan Giri, Krishna with his beloved ladies whilst the dwarapalakas guard the doorway.

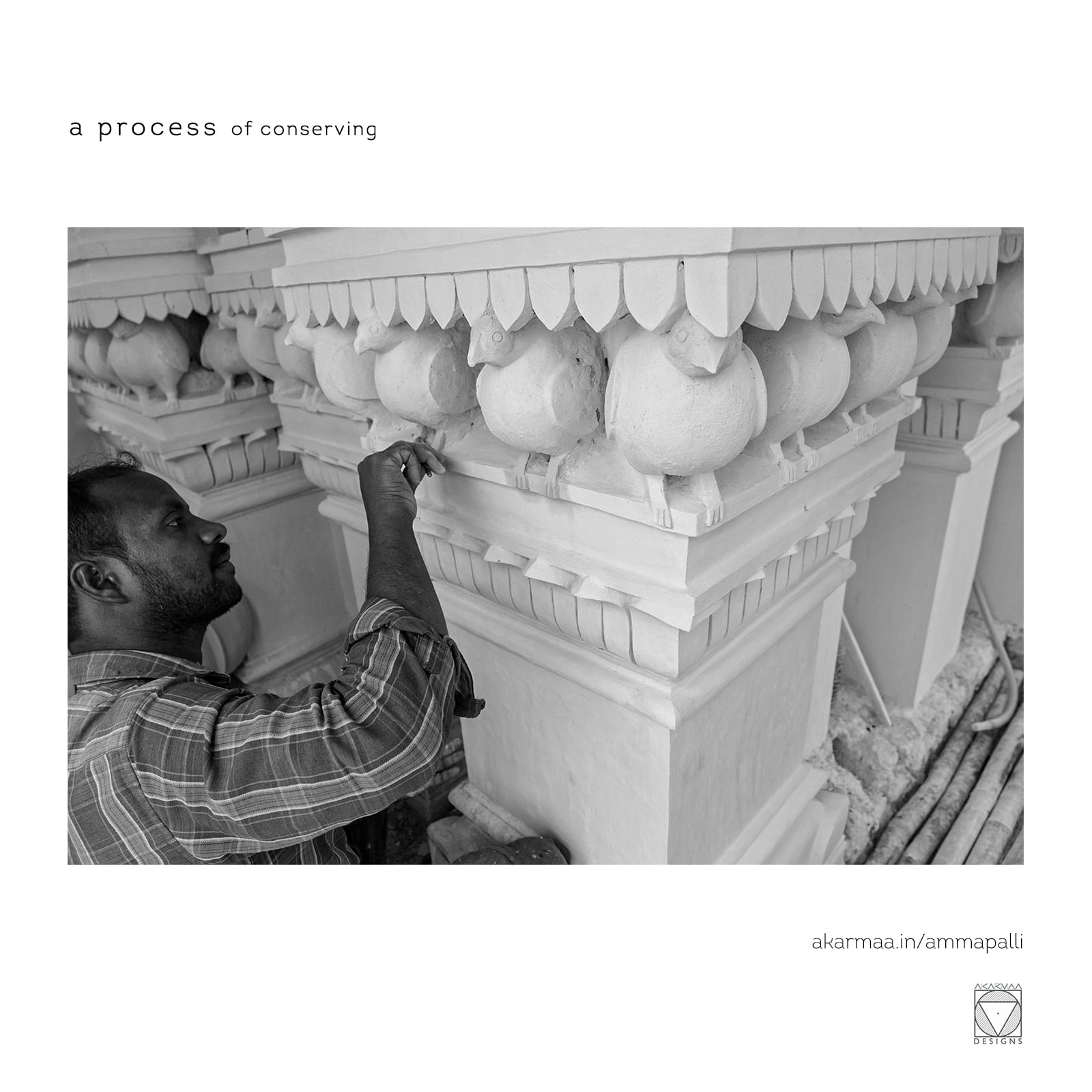

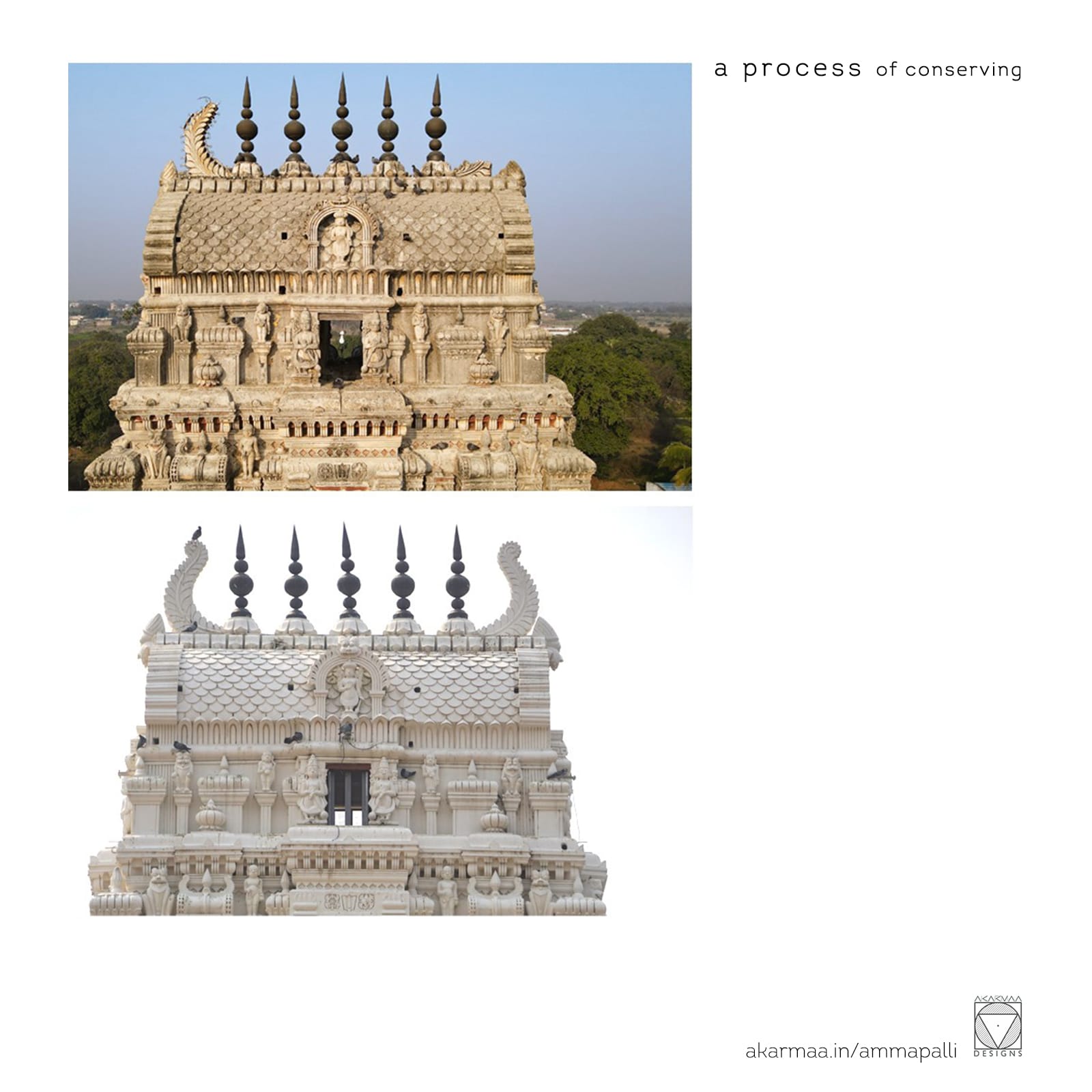

Breaking the conundrum of krishna tales, the third tier had reminiscence of the feet of a seated figurine which later came to light as the sculpture of a mother Lakshmi. Tiers 4, 5, and 6 are decorated with flowers, bells, dancers, angels, animals, and birds. The central part of Tier 7, the topmost and smallest of all with a vaulted ceiling is detailed with continuous alternate semi-circles in fish gills pattern, with the figurine of Lord Vishnu inset within a thorana; with hands blessing those walking through the gopuram. The upper surface of this tier is laid over with inverted flower stucco work to make a base for the Copper Kalashas to sit on top. On either side of the kalasha embellished with petals, two horns like kumbhams rise into the sky. To the side faces of the gopuram, kirtimukhams – the glorious face of a swallowing lion, that has ornate toranas borders the outermost edge of the 7th tier. There is also a flag hoisting pole-holder discovered as a part of the gopuram structure just below the centre of the top tier which was preserved.

Attributing to the understanding of the wind currents, the top two tiers have one Dwara (opening) along each direction, while the bottom ones till above the jharokha have one along the east and the west sides. Each Dwara is guarded by well-built Dwarapalakas (guards along doorways) armed with Gadhai (mace), with some carrying flags. Other designs unique to the gopuram are a dholak with a Kirtimukha, diamond-like grids like those of a pineapple, thoranas, kalashas and buds.

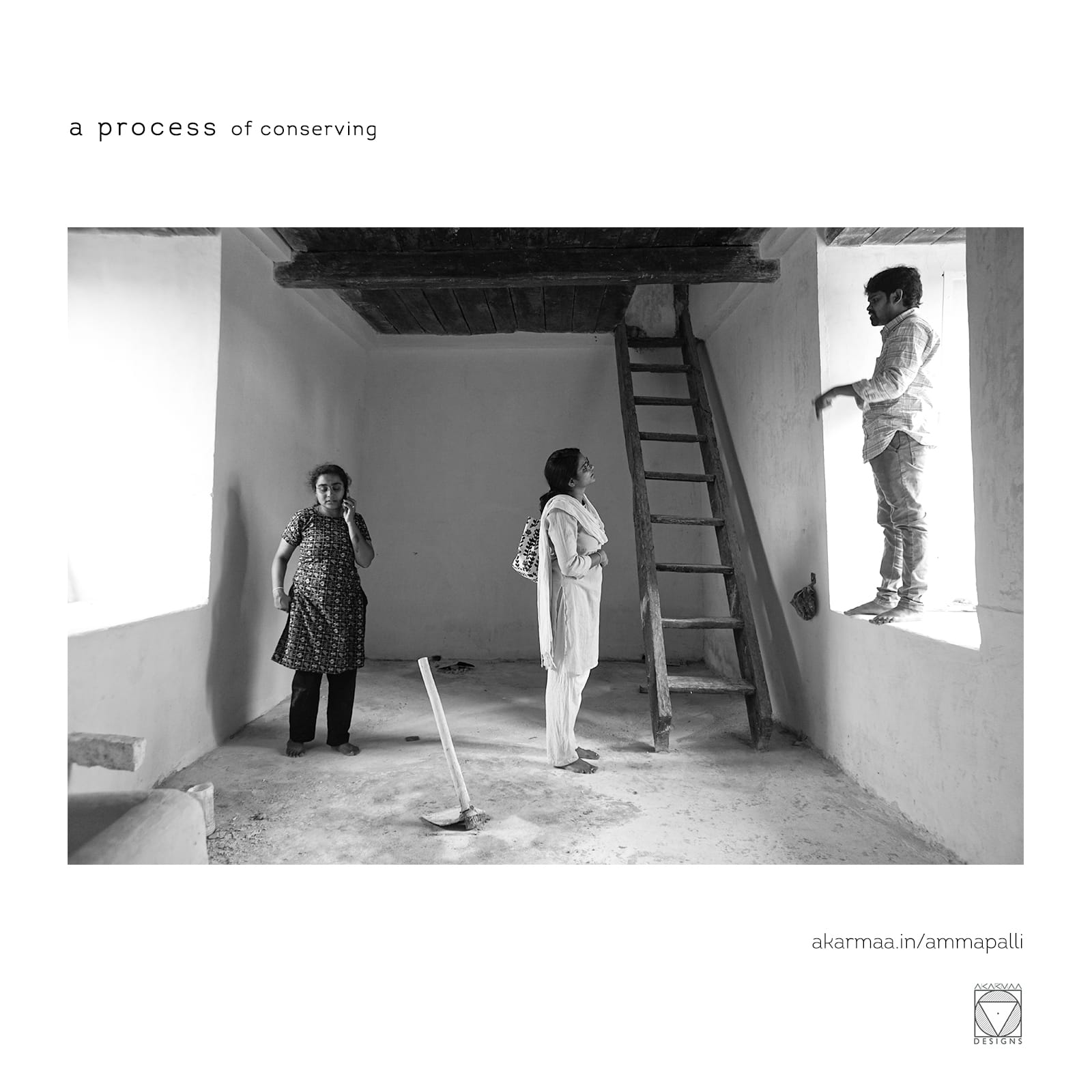

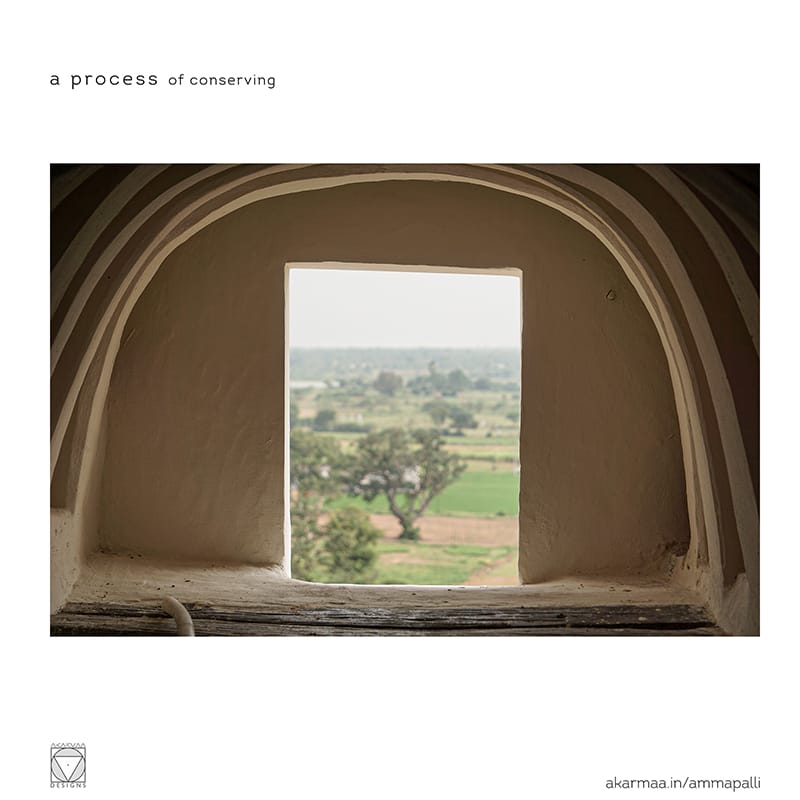

The inside of the gopuram is simple and functional with the base built with soft granite stone and above structures built with brick and lime. Wooden ladders connect one floor to another. As one climbs higher, the structure further becomes lighter and smaller, culminating in ribbed vaults atop. The different tiers, separated by wooden floorboards with lime-brick-bat on the inside, are ornate with bands of small brick brackets, floral bands and pigeons on the exterior facade. The eastern side of the gopuram is more detailed with stucco works while the rear and the two sides have ornamentation only on the upper tiers. A close inspection of the structure and the act of measure drawing revealed the simple coming together of small members to form this magnificent gopuram supported in a catenary form.

This gopuram exemplifies the plurality of expression in workmanship, with the Rajasthani style of sculpture accentuating the Bengali roof style of Jharokha. The sculptures here are less ornamented unlike the popular Dravidian style with broad faces, outlined eyes, thick lips and sharp fingers at the limbs. In-depth research and discussions with the artisans helped better understand the sculptural styles. It brought forth the dichotomy between the figurine’s body morphology indicating the understanding and robustness of the earlier crafts persons. The attire and instruments across all the sculptures; represented influences from the migrants.

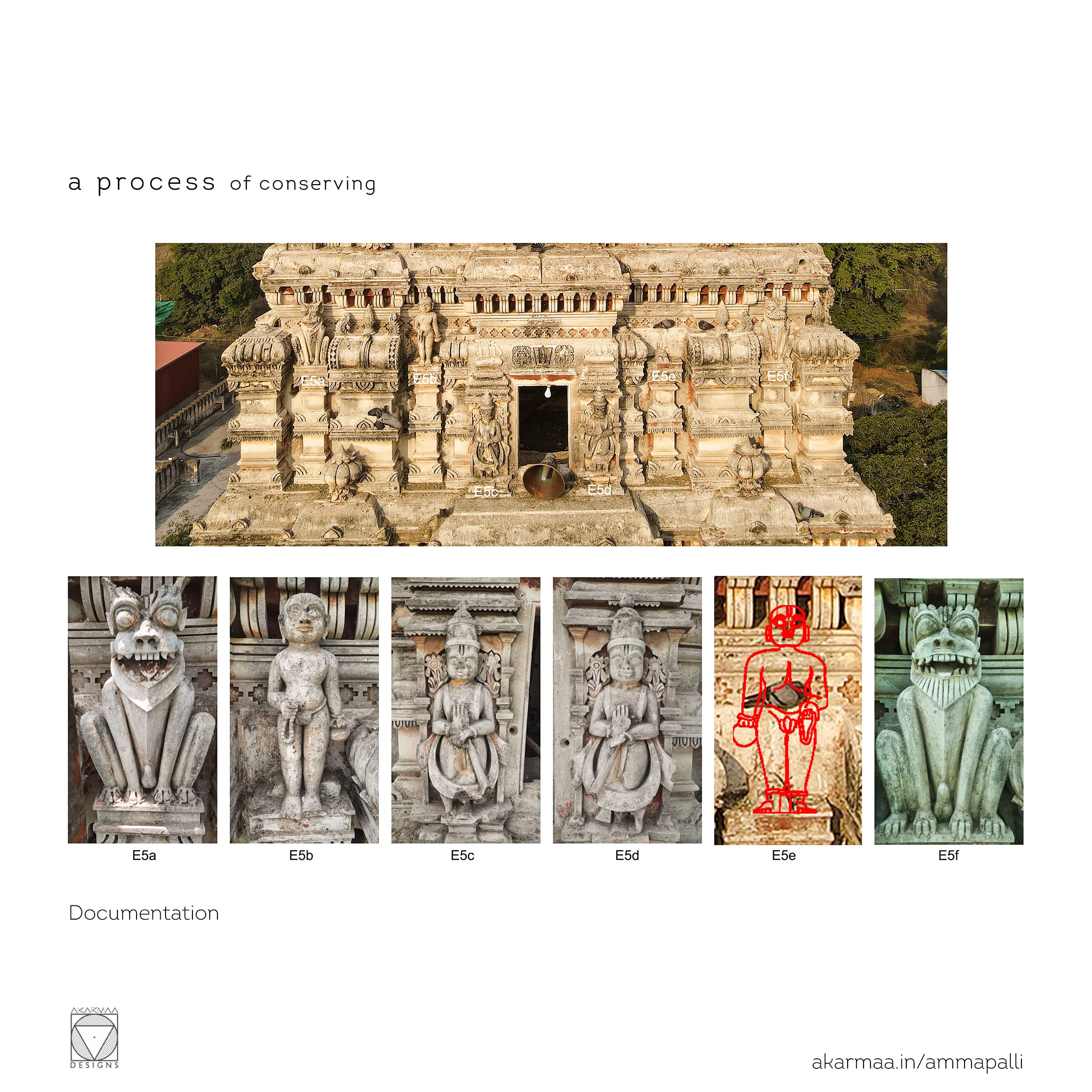

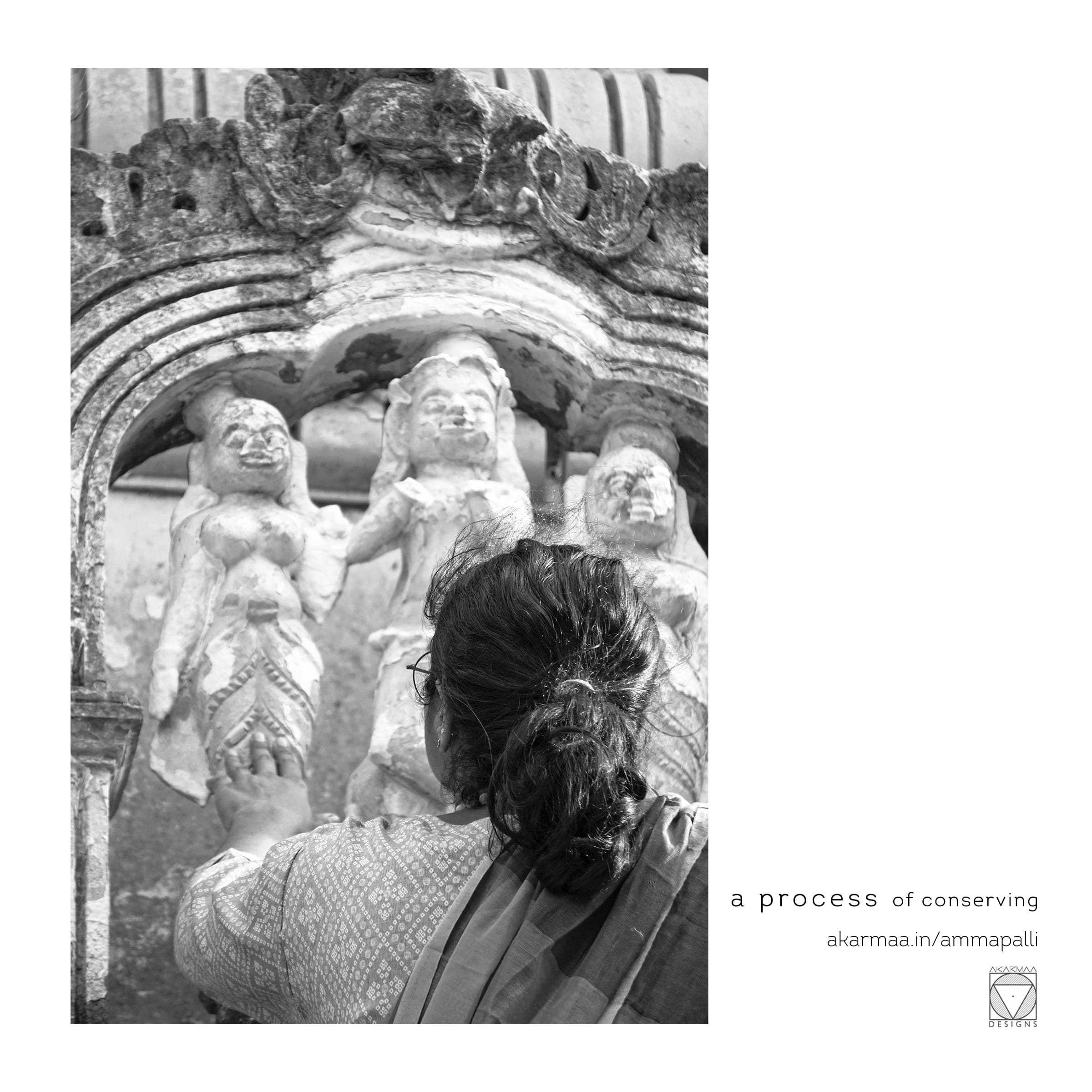

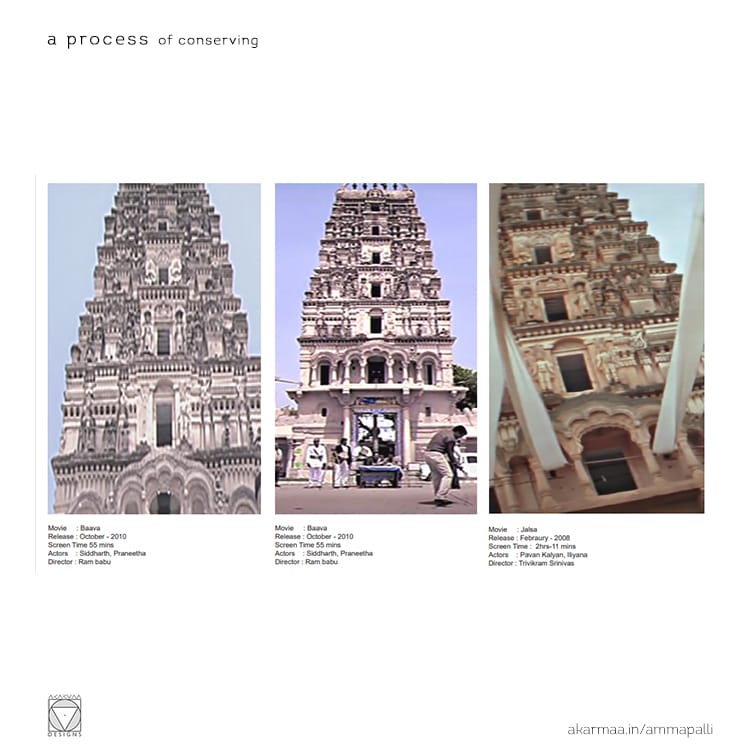

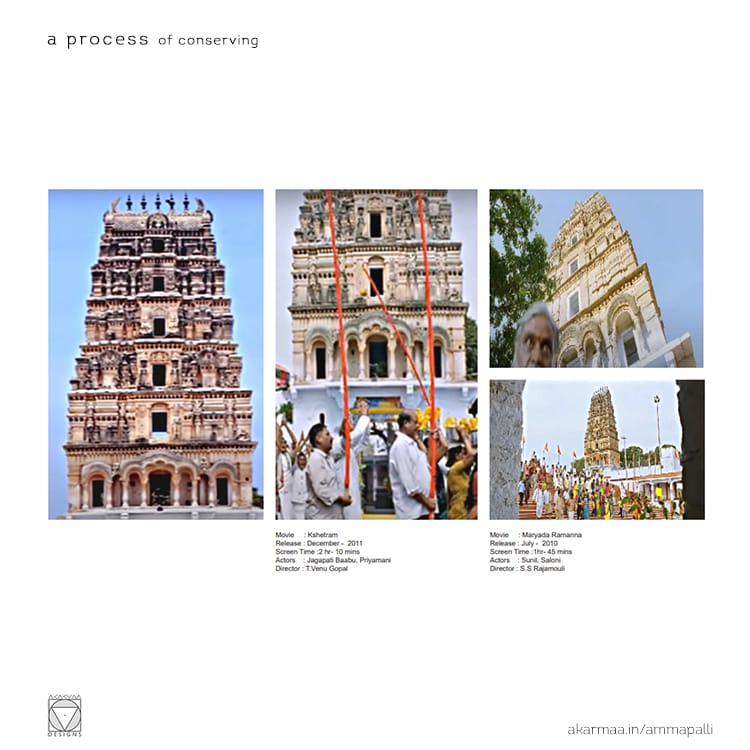

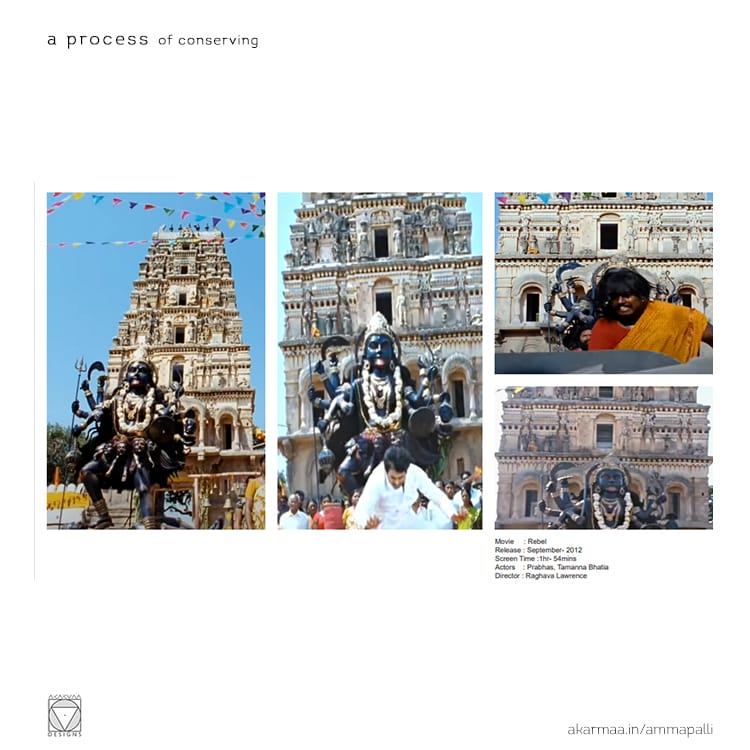

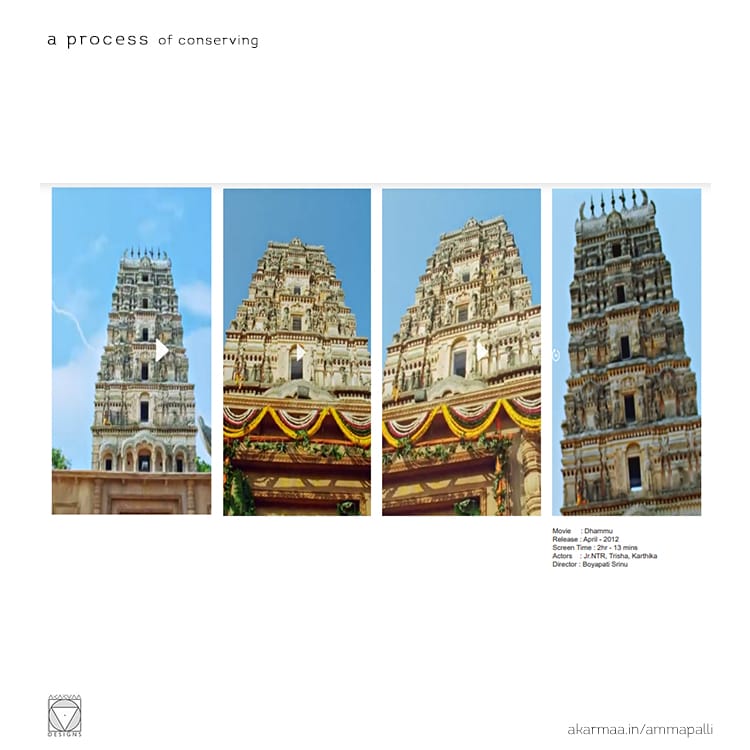

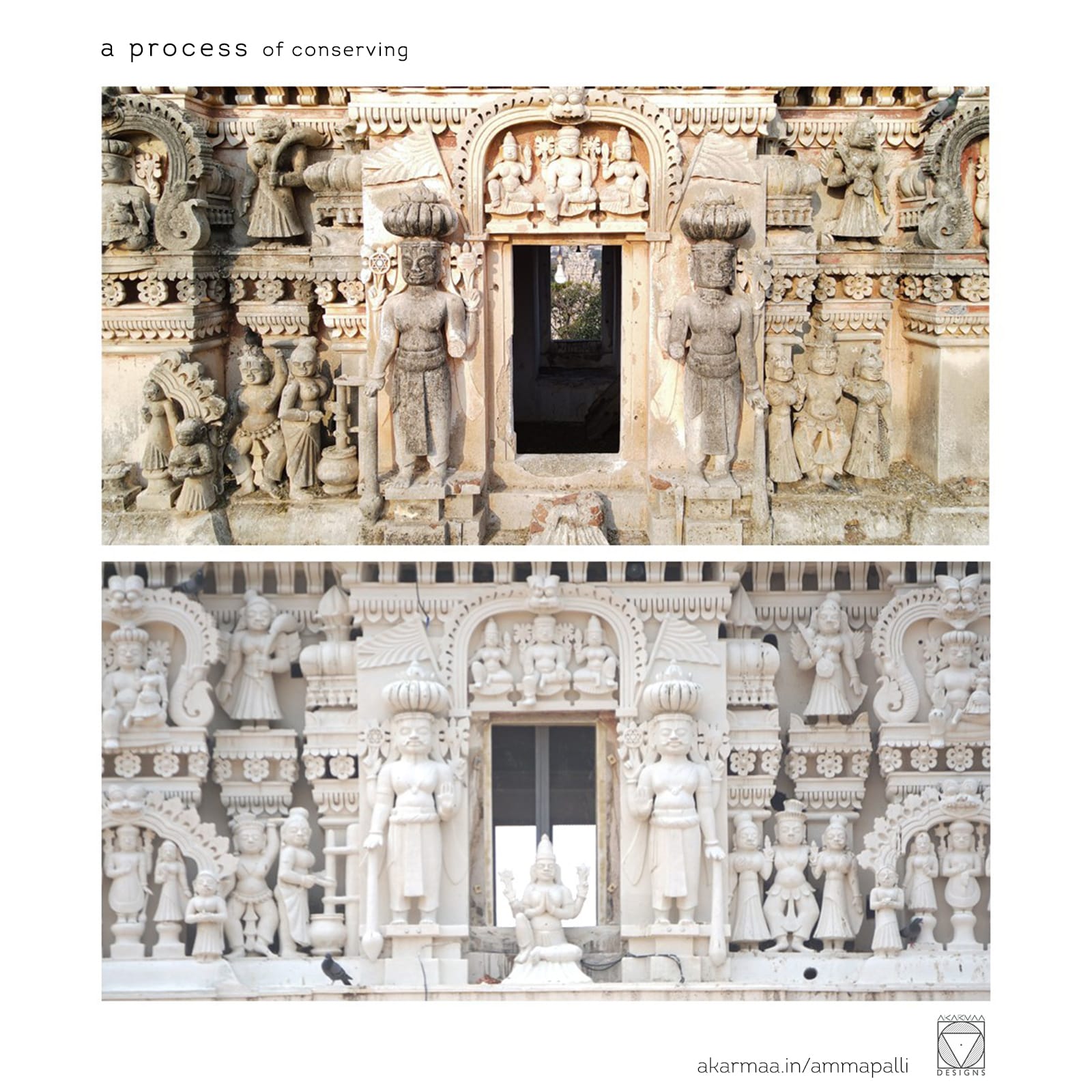

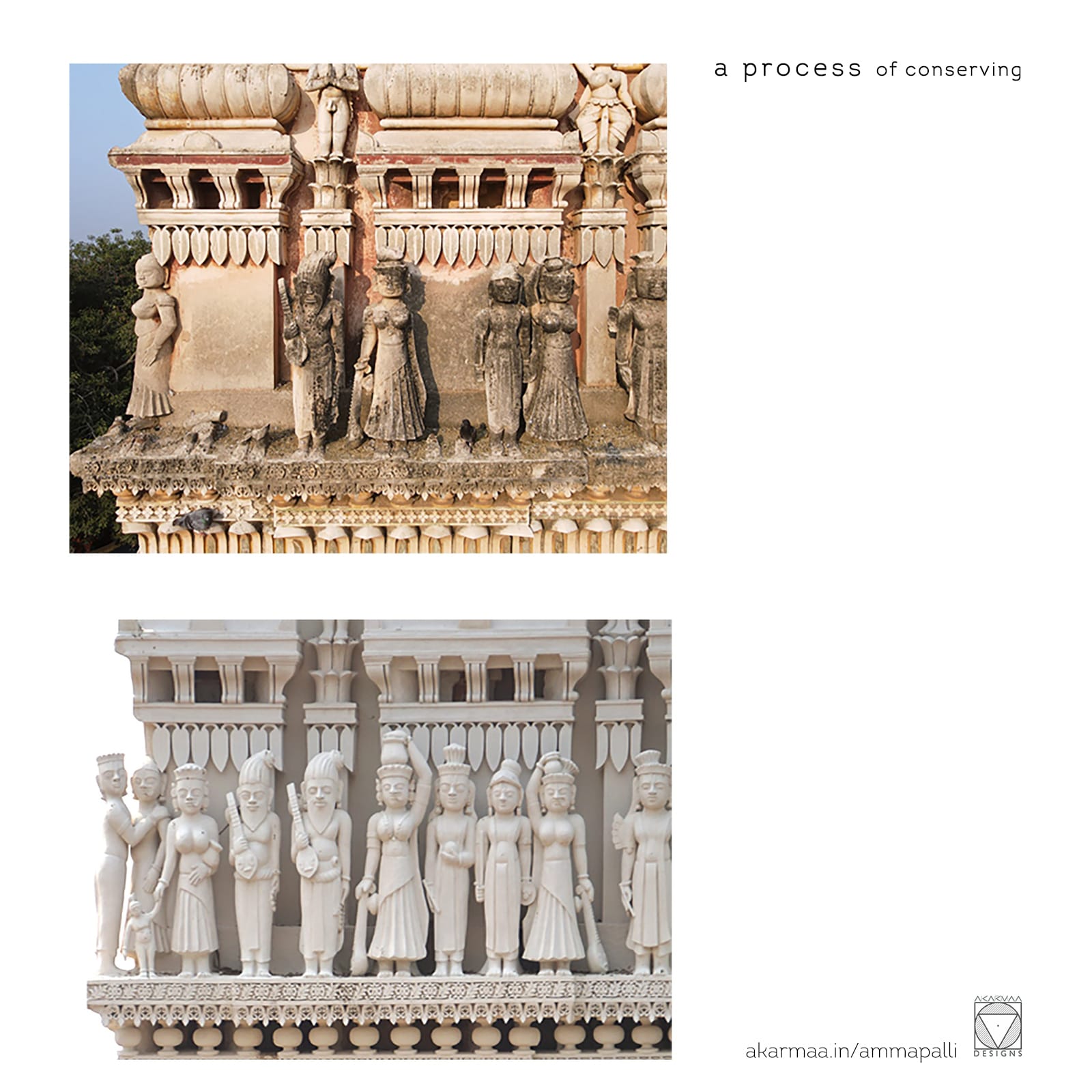

As there was not much-recorded data available, we attempted to understand through narratives of existing sculptures and motifs. Ar.Sreehitha analysed several movies shot in Ammapalli that had gopuram in their scenes to come up with chronological photo documentation, which formed the crucial part of the research to identify the missing sculptures in various tiers. Architects Renga, Keshav and Stephan measured the entire gopuram for documentation several times to get an accurate drawing. Like magic, hidden details of the gopuram started to reveal themselves slowly. The existing condition of the structure indicating growth of vegetation, uneven surfaces, water seepage, ingress, hidden cracks and damaged sculptures was documented ‘as is’ for assessment. Many new conditions surfaced after the initial cleaning process of the structure; structural cracks were identified and wooden lintels were found damaged.

While the architecture of the temple offers interesting insights about the people, their identity and the construction technology; the process of conservation revealed many possibilities leading to the condition at which the restoration process was taken up. There thus, is a fabric of narrations, woven by technology and tales; detailed by people’s faith and skill. The conservation process unveiled the correlation of the structure with the people and the gradually evolving identity of a place which has sustained the test of time, graciously adapting to the present-day needs.

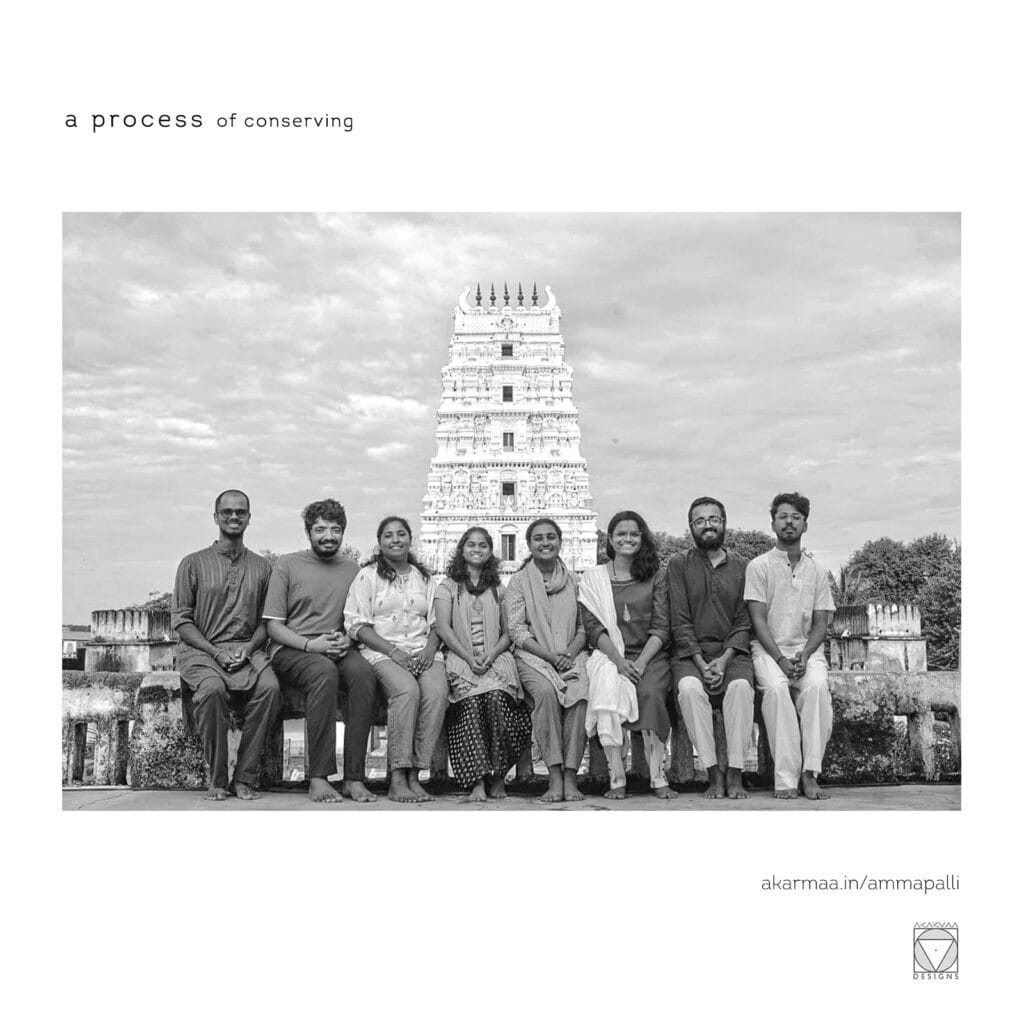

“There is one timeless way of building. It is thousands of years old, and the same today as it has always been. The great traditional buildings of the past, the villages and tents and temples in which man feels at home, have always been made by people who were very close to the centre of this way. And as you will see, this way will lead anyone who looks for it to buildings which are themselves as ancient in their form as the trees and hills, and as our faces are.” A team of architects from Akarmaa worked on researching and documenting this ‘quality without a name’.

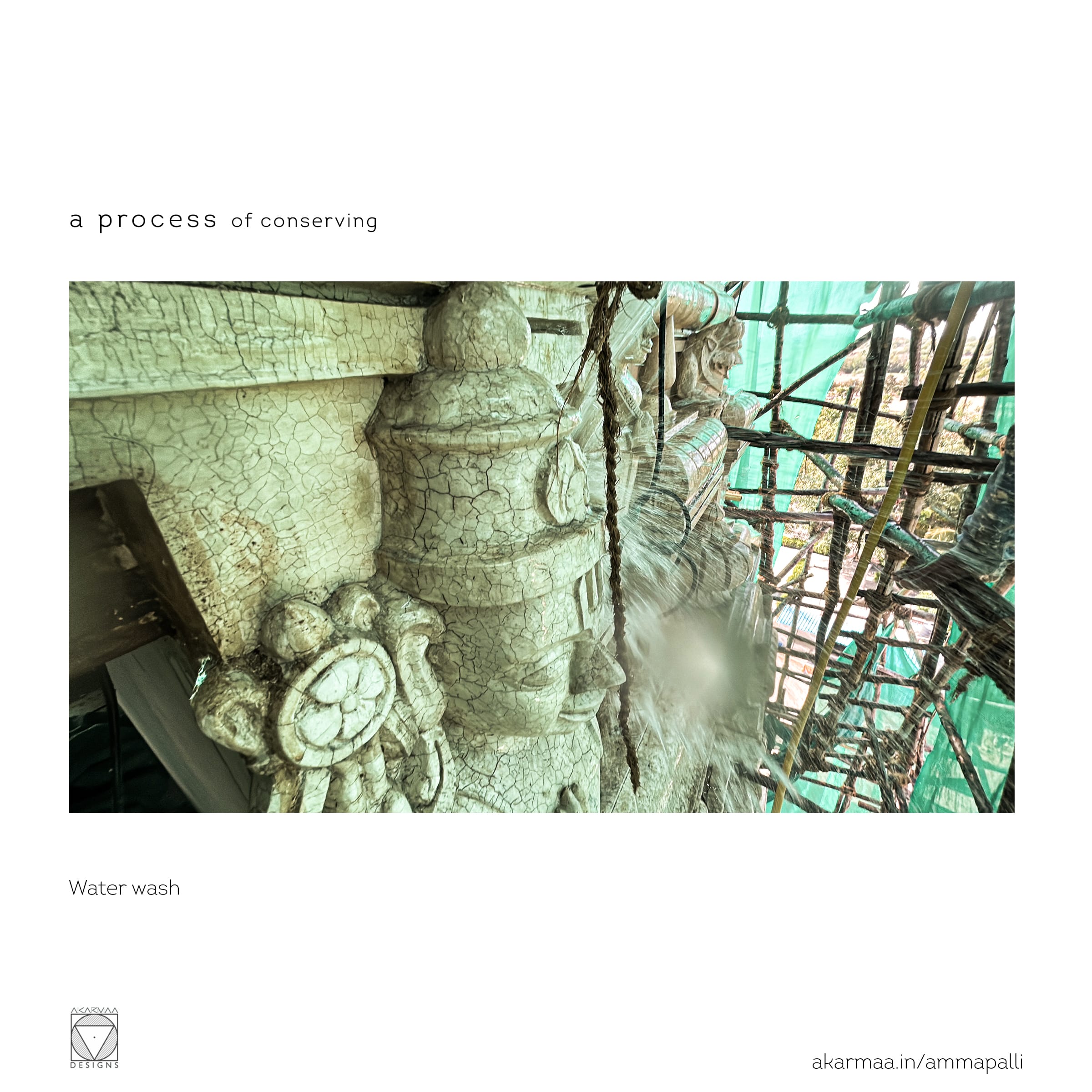

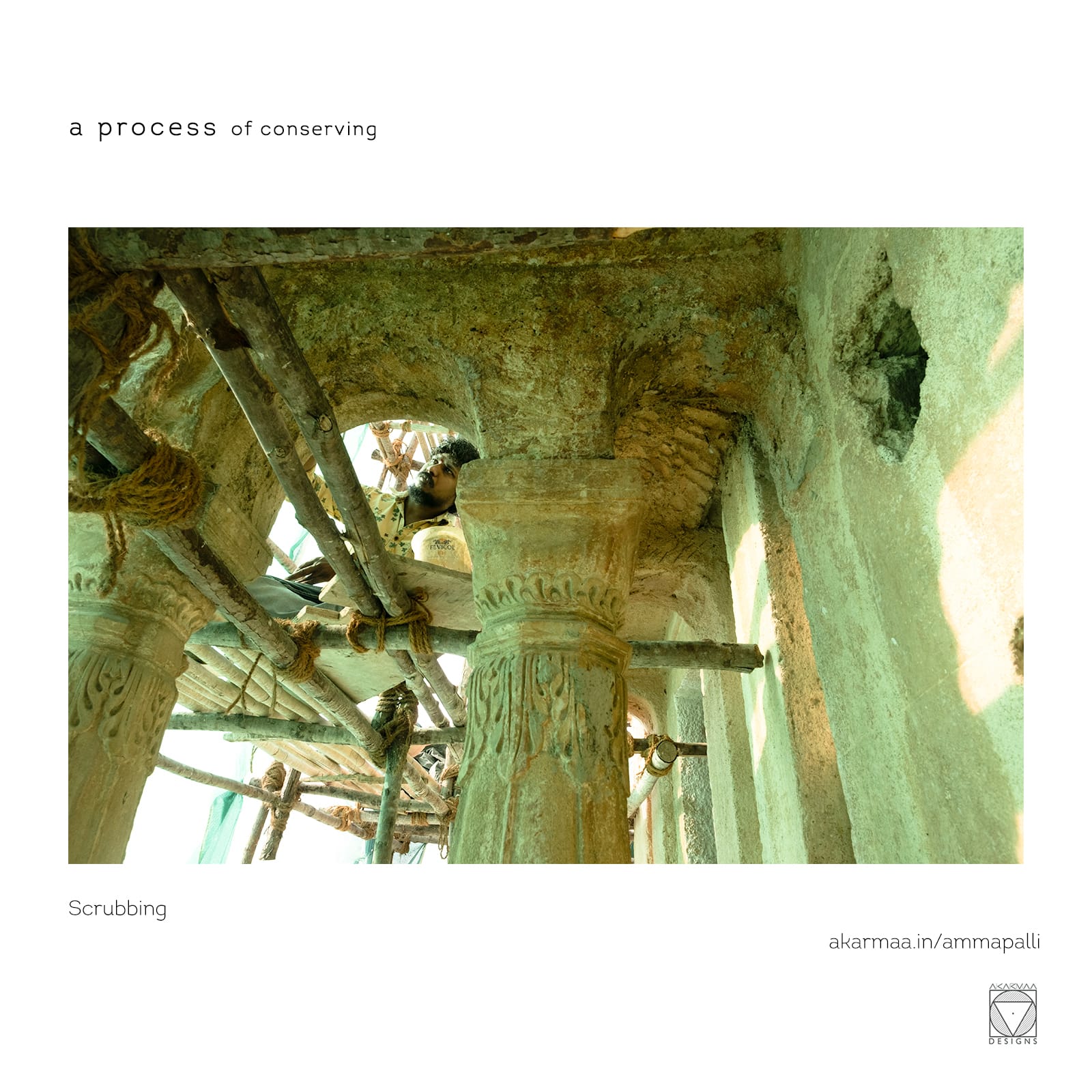

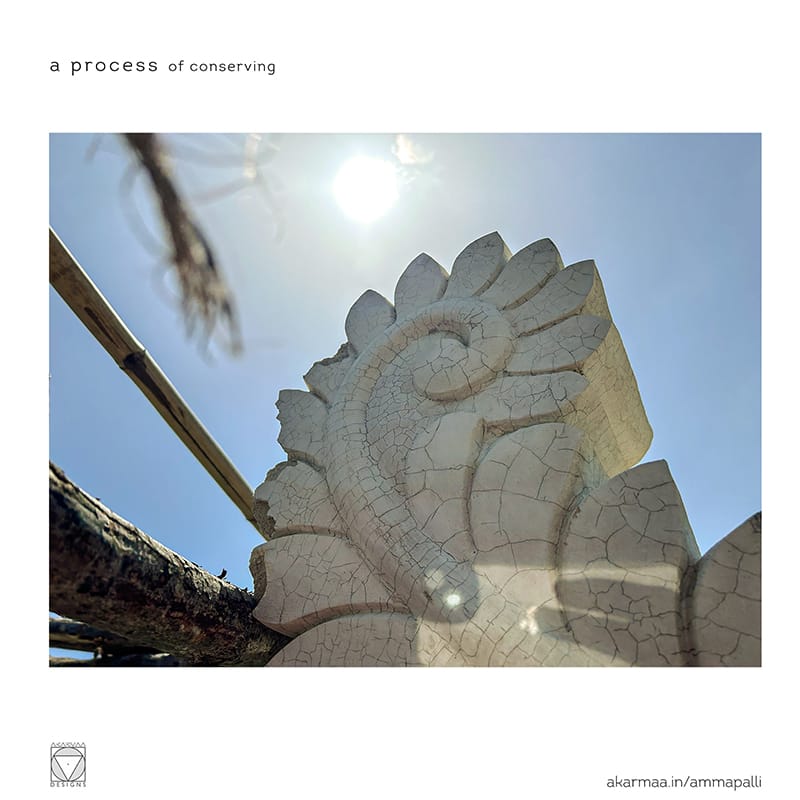

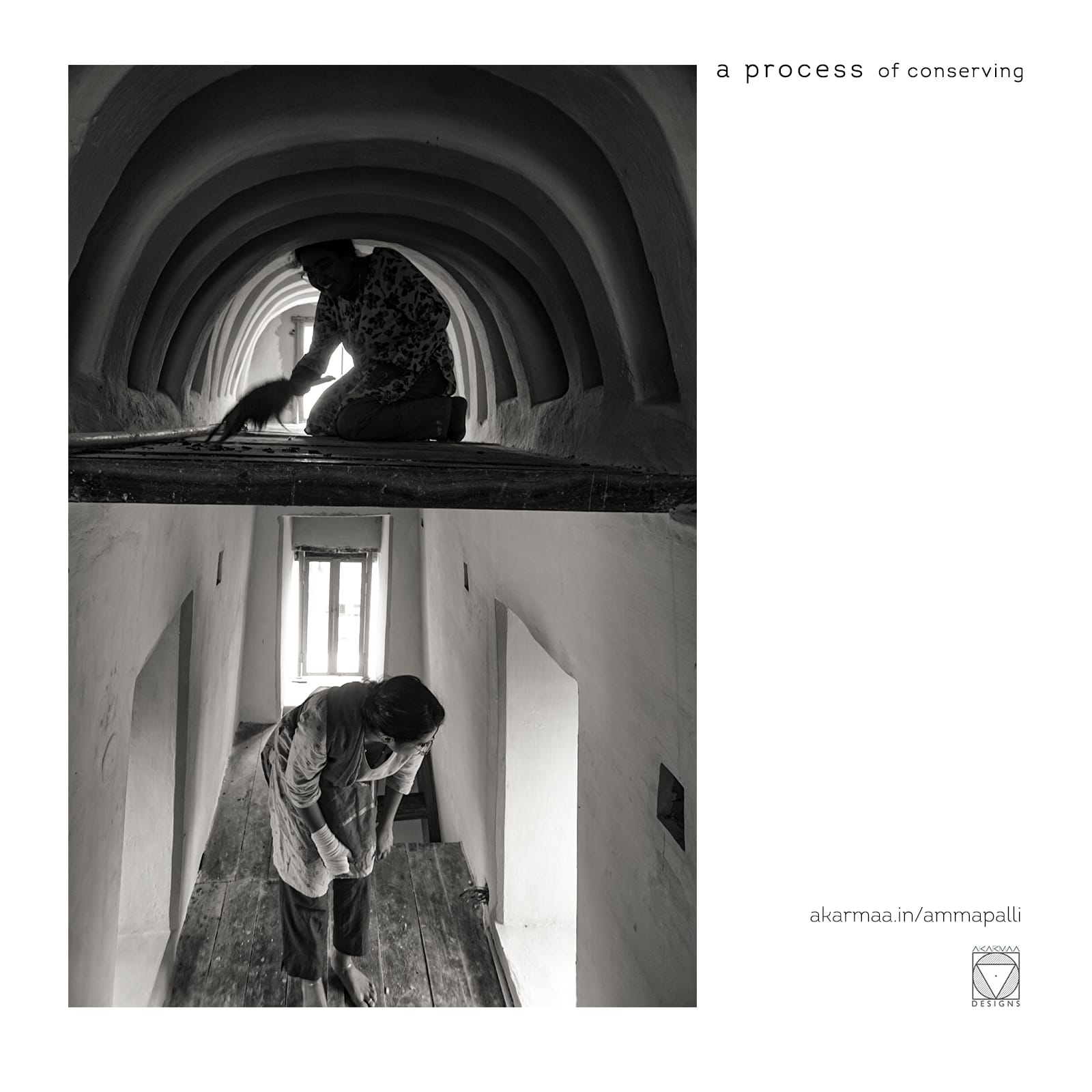

The first of the processes was to erect the scaffolding and ensure safety of the team of architects and workmen. The cleaning process involved freeing the structure of dead plaster and damaged materials followed by a water wash. In the process, traces of colours on attire and metallic pieces embedded in the ornaments were found. The top layer was chipped to remove several layers of loose paints and plasters, sedimented as a result of its past exposures. Many conjectures were derived such as the wooden log projected inside gopuram tiers could have been remnants of old scaffoldings left behind from centuries. The entire gopuram has mysterious holes on the wall surfaces which gathered many speculations and possibilities of use.

The conservation process was a conscious approach to authentically restore the structure while adhering to the present-day functional requirements. While all the materials used were checked for homogeneity, the new interventions were made reversible as per international conservation principles and UNESCO guidelines.

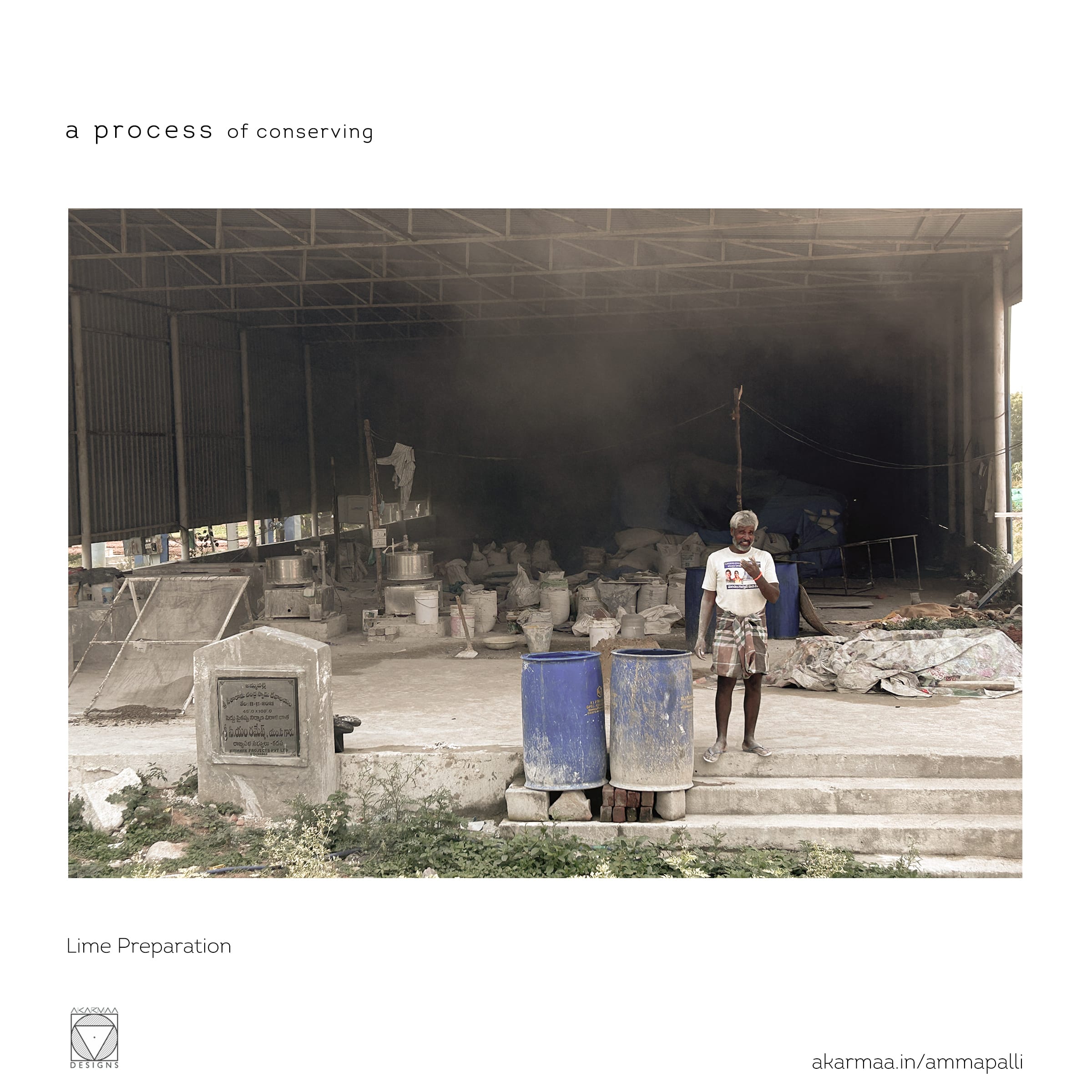

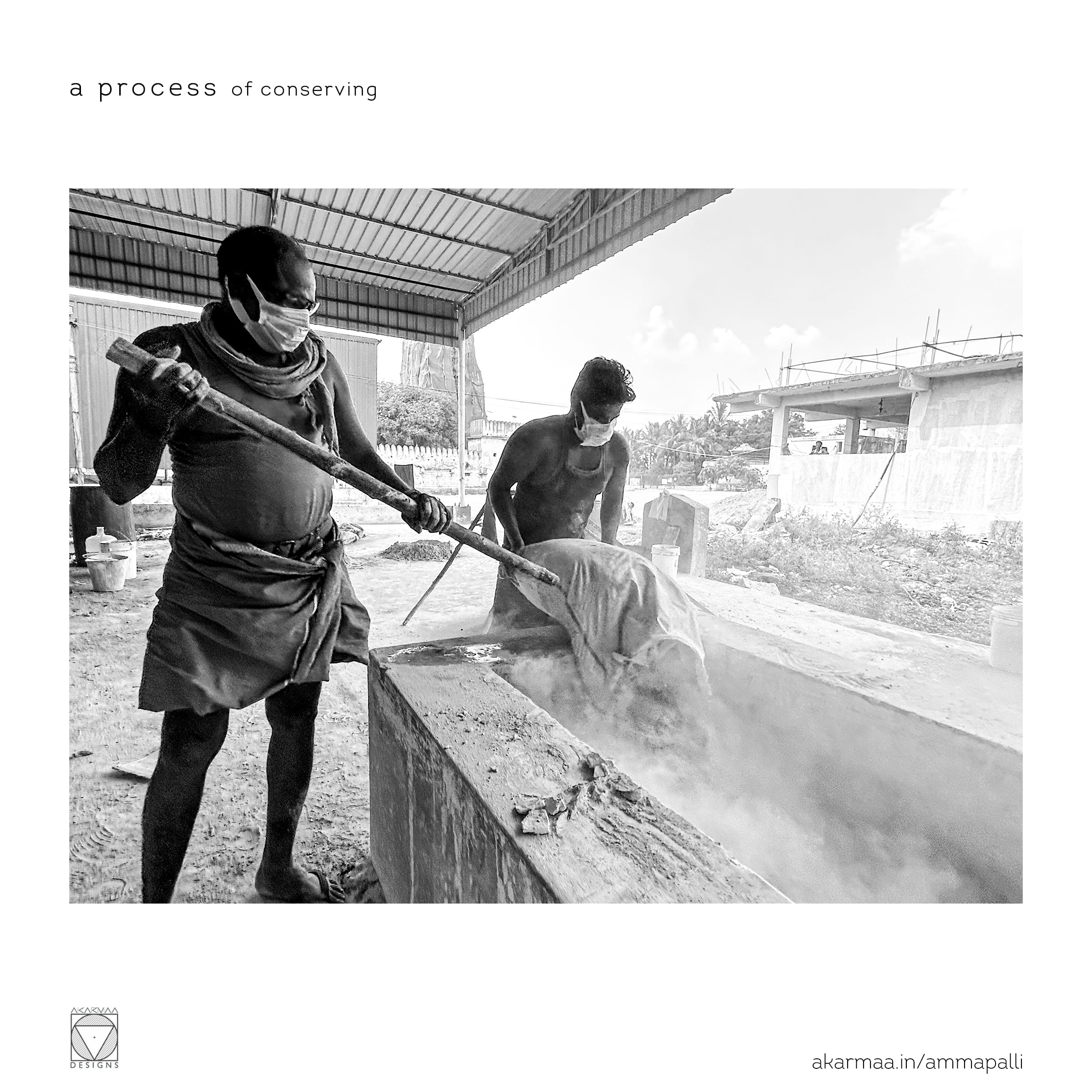

A shed nearby was dedicated to material preparation. Lime was slaked, flowered, mixed, ground and processed. Kadukkai was broken, boiled and watered. Jaggery solution was prepared in drums, sand was sieved. This shed was the heart of the entire process, working continuously to supply material.

A total of 11 lime samples were collected from different parts of the structure. Exposure to weathering, rain, sunlight, contributions from winged inhabitants and layers of the material were considered before choosing points for sample collection; this ensured accurate reports on material testing. Samples from nearby quarries were also sent to the lab for testing compatibility to the existing original material. Throughout the conservation process, about 53 lime samples using different combinations of lime, binding material, jaggery, kadukkai, and sand were explored; initially arriving at a similar proportion as of old lime used centuries ago and then to appropriate for the different layers of use. We learnt that with the use of pure lime, an added challenge was to protect the surface from absorbing colour from bird droppings. This required another round of sample making and testing. Sthapathi Venkat Reddy, Mr.Arun, Mason Gopal, Mr.Seetharam and Mr.Vidyanand supported us with deriving the lime compositions on site.

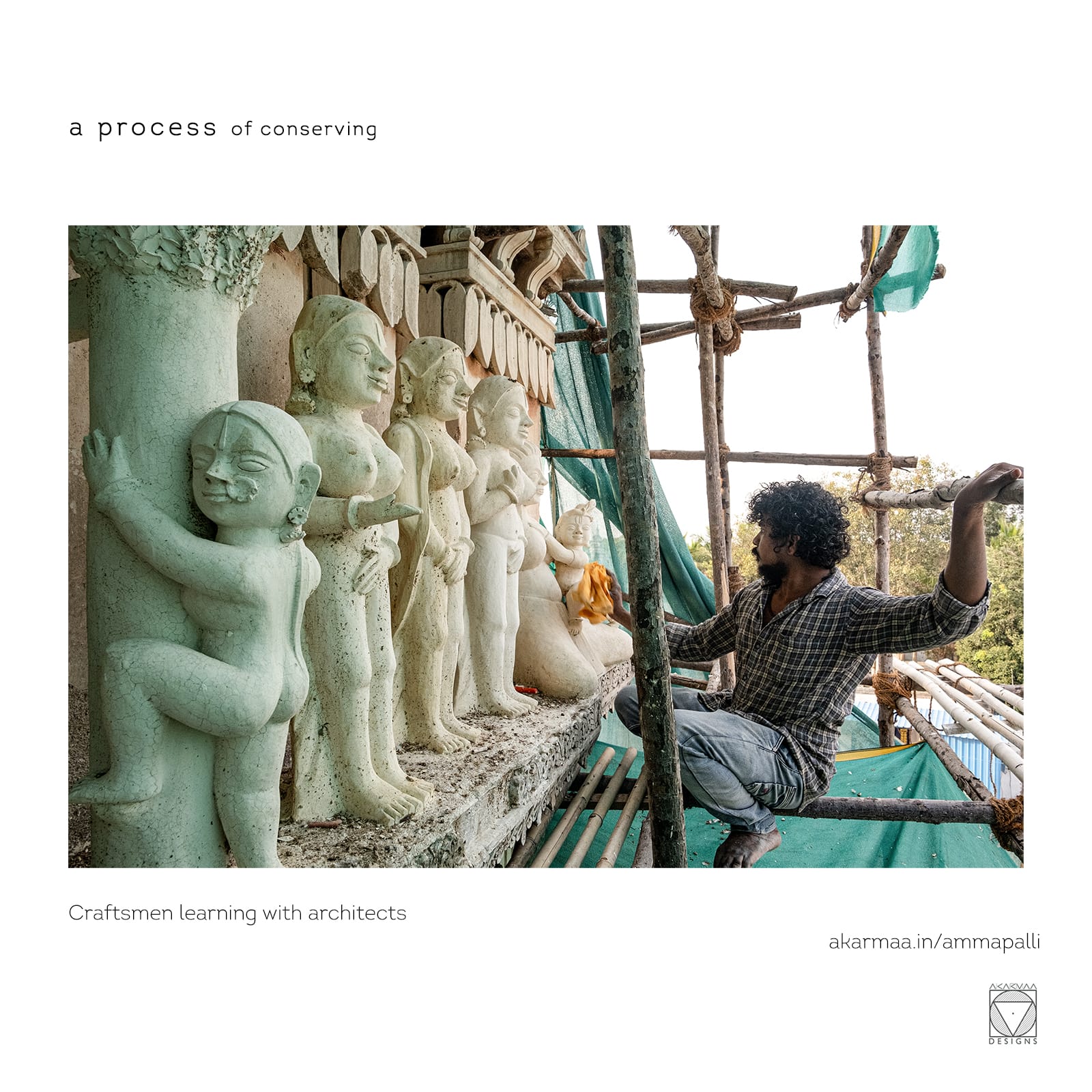

The Rajagopuram has about 124 sculptures, 223 Pigeons and many floral embellishments that adorn the structure. There were 30% sculptures with 10% damage, 25-30% were half broken, and the rest were missing. Sculptures were made of brick-bats and metal frames, moulded with mortar to give them the form desired. Many trials were also undertaken over two months to get the right proportion of sculptures restored. The restoration of sculptures, ornamentation and stucco work was done in pure lime by artisans from villages near Poompuhar, Tamil Nadu while plain-lime surfaces were undertaken by workmen from Kurnool, Andhra Pradesh.

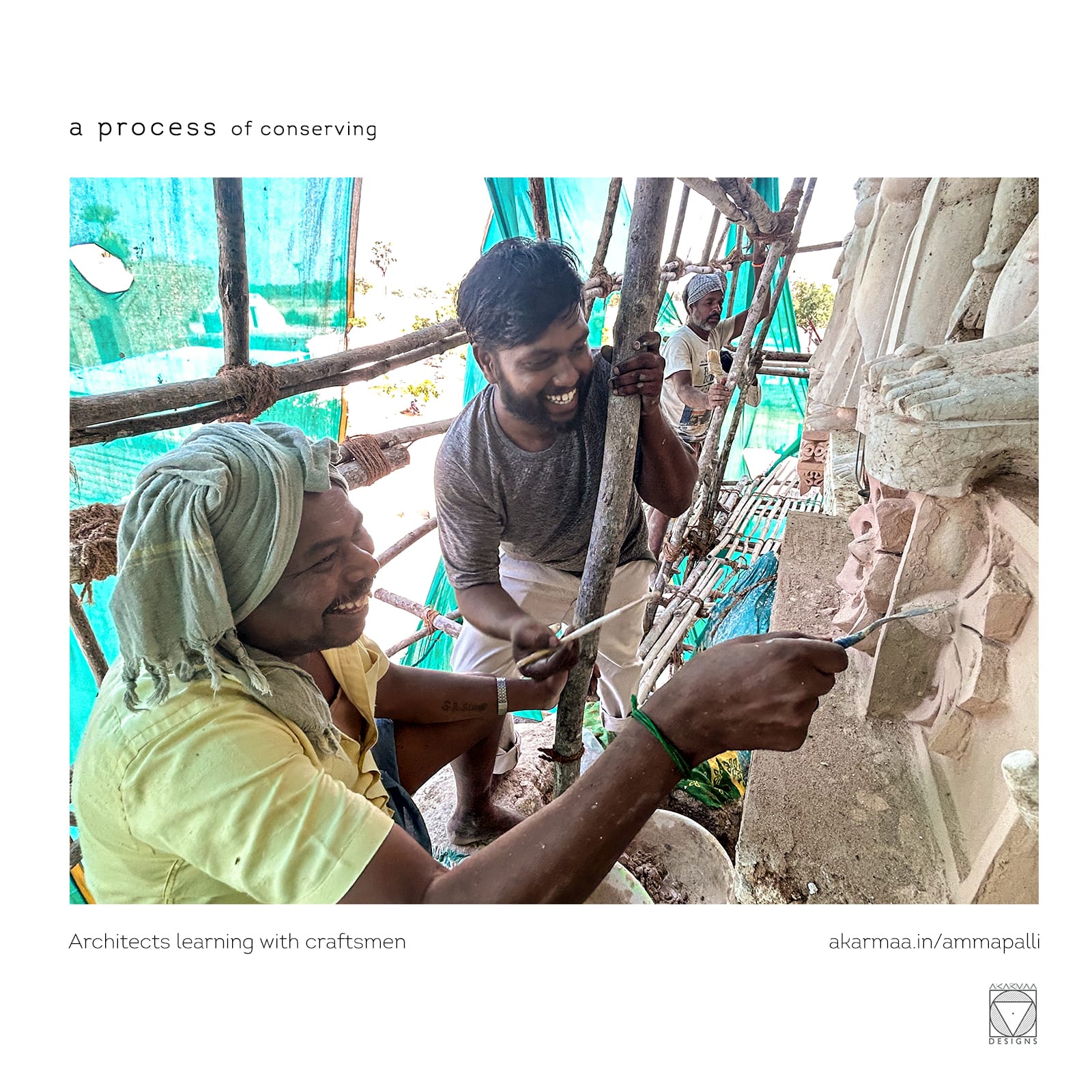

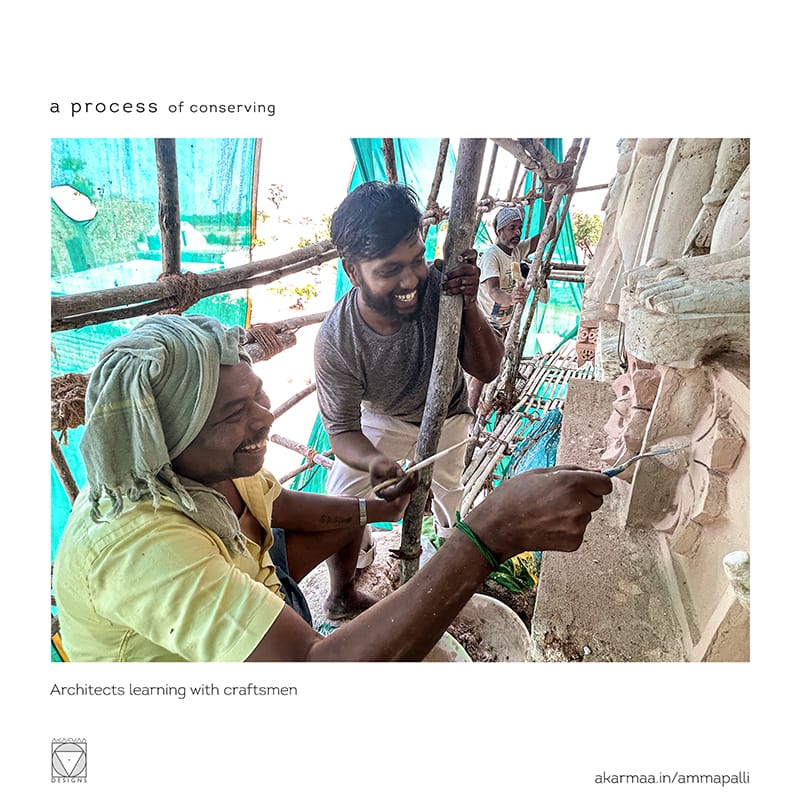

“Madam, can I make it better than this, more beautiful?” asked Jawahar, a lime craftsman extremely skilled with sculpture making of temples in Tamilnadu. In a memorable interaction, sitting on scaffoldings at 70’ from the ground, Ar.Arunima discussed tales of people and the landscape; how the environment and the food habits reflected on body morphology to explain how these sculptures are different from other places in south India with which the team was already familiar, with their curves, expressions and elements. There were a lot of unlearning like these, that the habituated muscle memory of craftsmen had to go through. The goal was not to make sculptures more beautiful; instead, it was to bring them back to their authentic state ‘as was.’

But with these added learnings they were extremely precise and integrated in their craftsmanship. Experienced local carpenters worked on the wooden rafters, flooring and lintel. Door shutters were made in cast aluminium and all the hinges were specially designed to be reversible in addition to the existing frames. The structural and member cracks were addressed with special adhesives and EN8 carbon steel respectively. A senior metallurgist from Hyderabad overlooked all the metal works.

Ar.Badri trained under craftsman Jawahar to learn the art of sculpting using lime. Using a crafting tool he measured body length, proportion, and details and through his learnings, he finally restored a sculpture of Bala Krishna, unassisted. Architects Divya, Rakesh, and Priyanka were trained by craftsmen Anil and Siddu in applying lime plaster on rough walls. In a day the interior of the mezzanine was completed and at the end of the day looking at their contribution they all had mouth full of smiles and handful of blisters. One fine morning while Ar.Sriraj was on site, he witnessed helper Ramulakka, bowing to her sculpting tools before work, which shifted his reverence towards tools of work.

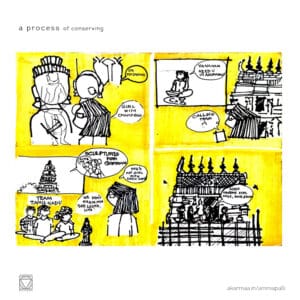

‘Removing the scaffolding from over a 100 height, and balancing through the process while ensuring touch-up of small incurred damage was of great challenge’ recounts Site Architect Priyanka, who had the rare opportunity every day of learning by doing on a 400-year-old structure. Ar.Priyanka also had several experiences on-site working with craftsmen and literally becoming one of them. Architect Stephan, gaining his first experience with lime, spent every day at the site as if it were a workshop to learn directly from the master craftsmen. Er.Akshitha was carefully chosing and collectiing lime samples for testing. Architect Hiranya, who worked on detailing the missing sculptures stayed at the temple along with Ar.Arunima for a night to observe the tranquillity of the place, in contrast to the bustling activity during the day. The night passed discussing the dreamy possibilities of the sculptures coming to life in the silent dark. All these dreams were captured into caricatures by Ar.Rakesh. Cats and dogs inspected our work often, while birds made their home even during the work, Bees took the freedom to build their hive.

For few it was working to feed their family, for some, it was their act of love, for some it was a learning expedition, for some it was their service to God but for none, it was just another site. Day by day, tier by tier, work was getting to closure.“Our hearts were pounding out of the rib cage; we were all thrilled” said craftsman Shiva after taking down wooden scaffoldings. Overwhelming tears glistened in our eyes as we saw the gopuram unveiling from behind the green mats that covered it for over 18 months, like pregnancy. The magical mix of traditional lime plaster changed its colour over time and became pure white. The gopuram started to look one amongst the clouds on a bright sunny day. This was made possible by the combined efforts of so many people and their collective goodwill.

The team at Akarmaa extends their heartfelt gratitude to all those who were involved and made this possible, for generations to come.

To our mentors Prof.Rabindra Vasavada, Ar.Khushi Shah, Dr.Neeta Das and Ar.Ajit Rao.

To Prof.Shorey, Artist Nikitha, Ar.Nithya, Arun and Shalini who made time to visit us on site.

To Ar.GopiKrishna, Ar.Vivek Eaadara, Ar.Kausik for photography and

Vinod Baluchamy for videography; at different stages.

To Anuradha Reddy Garu (INTACH Convenor), Shivanagi Reddy Garu (Archaeologist), Vinodh Kumar Gaaru (Temple trustee), Vallinayagam Sir (Sthapathi, Endowments Department), Krishnam Raju Garu (Researcher), senior members of the local community whose inputs helped in architectural conjecturing and to understand the multiplicity of co-existent histories.

To Architect Bhavana for this learning opportunity.

To the donors who initiated and funded the conservation project.

To Dr.Thirumalini Selvaraj for supporting the material testing.

To team from Aayadi Nirman for helping with traditional craftsmen.

To people from Akarmaa and Cuckoo family for their being.

To all the craftsmen, masons, helpers, electricians, carpenters, welders, cooks and

entire team who made it possible, beyond all hurdles.

To everyone who is not in this list, but had contributed in someway.

To baby Kairav, the youngest member accompanying the architects and craftsmen onsite, who firmly believes that the entire gopuram is carried on the back, by all the pigeons in stucco.

Maybe it is!

We still wonder if pigeons from the Gopuram were being messengers and what messages would they carry now?